David Beckworth has an excellent interview with The President and VP of the Minneapolis Fed. I did a post on the portion of the podcast that interviewed Neel Kashkari, over at Econlog. Here I’ll address the part where David interviewed VP Ron Feldman, mostly on banking regulation. I’ve always thought that eliminating moral hazard is the only way out of this mess. Feldman says that’s politically impossible:

I think you just need to look at what happened with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. This was in a prior regime. People used to talk about what’s called subordinated debt, but it’s the same idea, that they would be forced to issue debt that would be very junior, so it would get converted, and there would be no problem.

Now, flash forward. You’re in a crisis, and what people are worried about is, am I going to lose my money? You’re in the middle of a crisis, and you’re telling me that the solution to making people feel comfortable, not freaking everybody out, is that you’re going to impose more losses on more people. It just seems implausible.

The only active creditor in the US where we have a record that we do impose losses on them is equity holders. We do treat equity holders differently from fixed income holders, depositors, or bond holders. I think CoCos and bail-in debt, it’s very elegant. If it worked, I think that would be great. But we have a record of it here.

I should just add, in Italy and other places, they’re using the same idea. Last year, they were confronted with this issue: what are they going to do about the bail-in debt of the Italian banks that are in trouble? They said, “We want a special exception. We’re going to need to protect those folks.”

I think that’s the history. We talked about, is the five-year delay credible? The thing that’s not credible is that in a crisis, a government is going to want to impose more losses on debt holders.

Just to be clear, I don’t think it would be a problem doing this in a technical sense. Crisis or no crisis, there’s no reason why bonds can’t be converted to equity when a bank gets into trouble. But I suspect he is right about the politics, at least in highly corrupt countries like Italy and the US. (Perhaps it would work in the Nordic countries, or Canada.)

I find this to be profoundly depressing, and pushes me toward reluctantly supporting tighter bank regulation, especially higher capital requirements. The Minneapolis Fed has developed a plan that calls for a 23.5% capital requirement for large banks:

We would require banks to fund themselves with equity that would be equal to 23.5 percent of their risk-weighted assets. Risk-weighted assets means there’s a bigger weight that’s put on something, an asset that’s risky, and a lower weight that’s put on something that’s safe, like a Treasury bill.

I actually think the main problem is reckless smaller banks. That’s where our tax dollars go. I’m much less worried about the bigger banks, where moral hazard is less of a problem. Unfortunately, it seems like higher capital requirements are just as politically infeasible as reducing moral hazard through convertible bonds:

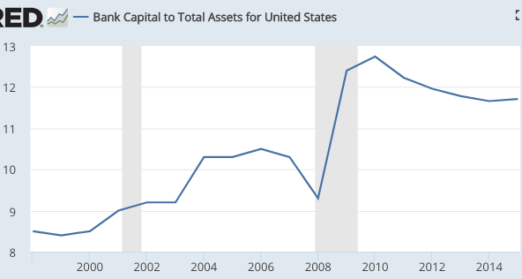

The capital ratio rose from 10.5% before the crisis to 12.7% after, but has since slipped back below 12%. A 23.5% ratio sounds great, but only if applied to all banks, not just large banks. Unfortunately there’s probably almost zero political support for doing some something like this.

The capital ratio rose from 10.5% before the crisis to 12.7% after, but has since slipped back below 12%. A 23.5% ratio sounds great, but only if applied to all banks, not just large banks. Unfortunately there’s probably almost zero political support for doing some something like this.

As with healthcare reform, as with zoning reform, as with FAA privatization, as with a hundred other issues, there’s simply no interest in banking reform. In either party.