Arnold Kling has a new article on monetary and fiscal policy. Because he slightly mischaracterizes my views, I should probably respond:

Scott’s argument for monetary dominance is that the Fed, which sets monetary policy, is way more agile than Congress, which sets fiscal policy. It’s like a game of rock, paper, scissors in which if Congress shows rock, the Fed shows paper. Or if Congress shows scissors, the Fed shows rock. The Fed can always win.

I do think the Fed is more agile, but the decisive factor is that the Fed is much stronger. If you want a metaphor that is better than rock, paper, scissors, imagine I’m driving my car and my 6-year old daughter pushes the steering wheel to try to change direction. I’d simply push back more strongly.

I believe in fiscal dominance. That is because I do not think that Peter cares all that much whether he hangs on to his T-bill or exchanges it for money. Scott thinks that Peter will spend more in the latter case. I am skeptical.

This isn’t the right thought experiment. I don’t doubt that if you give the average person a briefcase with a million in cash they’ll go on a shopping spree, and that’s equally true if you give then a million dollars in T-bills. That’s not the issue. Money is special not because it is regarded by individuals as wealth, rather because it is the medium of exchange.

If you add more cash to the economy than people want to hold, they can get rid of the excess cash balances only by pushing up the price level. In contrast, if you add more T-bills than people want to hold, they can drive down the price of T-bills, with no change in the price level. You merely need to assume that they aren’t perfect substitutes. (At least when nominal interest rates are positive, and Arnold seems to be arguing for fiscal dominance even during periods where interest rates are positive.)

Scott, like almost all mainstream economists, sees inflation as having a continuous dose-response pattern. Give the economy a higher dose of money and it will respond with higher inflation. Other economists measure the “dose” as the employment rate.

I think of inflation as an autocatalytic process. Inflation is naturally low and stable. But it can be jarred loose from that regime and become high and variable. Then it takes a lot of force to bring it back to the low and stable regime.

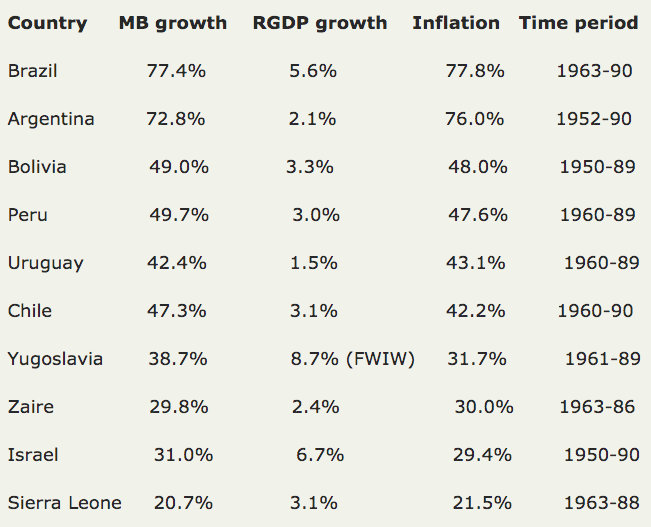

Nominal variables don’t have natural rates. It’s a policy choice. Inflation was not low and stable for most of American history, but became low and stable after 1990, when the Fed decided to target inflation at roughly 2%. These things don’t happen automatically. That’s why most central banks have set inflation targets, to prevent this:

Here’s Arnold:

Once inflation gets going, the only way to stop it is to slam on the economic brakes. Usually, this means drastically cutting government spending. But in the U.S. in the early 1980s, we slowed the economy without cutting government spending. Instead, the foreign exchange market put on the brakes by raising the value of the dollar, stimulating imports and making our exports non-competitive. And the bond market put on the brakes by raising interest rates, so that nobody could afford the monthly payment on an amortizing mortgage. After a few years of high unemployment, inflation receded.

Most economists attribute these developments to Fed policy under the sainted Paul Volcker. Scott could say that this was exhibit A for monetary dominance. The economic consensus may be right, but I would raise the possibility that the financial markets were the main drivers.

The price of goods (CPI) the price of foreign currency (E) are two ways of measuring the value of money (actually its inverse.) Here Arnold is saying that monetary policy did not make the dollar strong, a stronger dollar (exchange rate) made the dollar stronger (purchasing power). OK, but the two most plausible theories for the strong dollar were tight money and fiscal deficits. Obviously, Arnold is not saying that big fiscal deficits brought inflation down in the 1980s.

Exhibit A? Volcker was perhaps Exhibit J for monetary dominance; there are so many other examples that one hardly knows where to begin. Remember LBJ raising taxes and pushing the budget into surplus in 1968 in order to bring down inflation? How’d that work out? Budget deficits were pretty low in the 1970s, as a share of GDP. What happened to inflation? Then inflation fell as Reagan pushed the deficit much higher. A big reduction in the budget deficit from $1061 billion in calendar 2012 to $561 in calendar 2013 should have slowed the economy according to the fiscal dominance theory. Instead NGDP growth sped up in 2013. Then the deficit ballooned to a trillion dollars in 2019, and yet inflation stayed below 2%.

Overseas you find the same thing. Japan runs some of the biggest fiscal deficits ever seen in peacetime from the mid-1990s to 2013 and both the price level and NGDP actually fell. Then a new government switched to fiscal austerity and monetary stimulus, and NGDP begins rising (albeit still too slowly.)

Sorry, but fiscal dominance is not remotely plausible, at least with positive interest rates and an independent central bank.

Almost every major school of thought—monetarist, Keynesian, and Austrian, etc.—believe that monetary policy has a major impact on nominal variables. The financial markets respond to monetary policy announcements as if they are extremely important, often adding or destroying hundreds of billions of dollars in wealth within seconds. The history of economics is full of examples of monetary dominance over fiscal policy. Basic theory predicts that a $100 bill is not identical to a T-bill yielding 2% interest; otherwise they’d have the same yield. If Arnold Kling and the MMTers want to convince the me, the rest of the profession, and the financial markets that open market operations don’t matter when interest rates are positive, they are going to need something better than dubious thought experiments about the substitutability of cash and T-bills.