There is a new post at the St. Louis Fed that is purportedly about NGDP targeting, but actually is about . . . well I’m not sure what it is about. At times Daniel Thornton seems to be discussing instrument rules (where to set the fed funds target), and at other times he seems to be discussing targeting rules (NGDP vs. inflation targeting.) Consider the opening paragraph:

Old debates about the use of rules versus discretion for conducting monetary policy and the efficacy of nominal gross domestic product (GDP) targeting have recently returned to the forefront of monetary policy discussions. The economics profession has largely sided with rules over discretion, while the debate about nominal GDP targeting continues. However, despite the support among economists for policy rules, transcripts of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings suggest that the Federal Reserve has never used a policy rule, and there is no evidence that any other central bank has either. On the surface, a nominal GDP-targeting rule would seem easier to agree on and, hence, more likely to be adopted. However, this essay discusses reasons policymakers have not used policy rules and are unlikely to target nominal GDP.

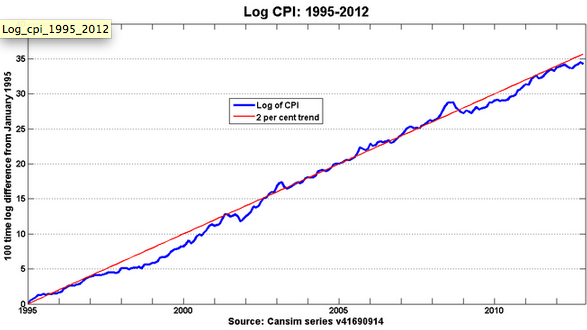

Now obviously lots of central banks have adopted various sorts of rules, just not the sort that Thornton seems to consider rules. The Fed adopted a rule of stabilizing gold prices at $20.67/oz, from 1914 to 1933. Under Bretton Woods many central banks fixed their currencies to the dollar. More recently, Canada adopted an inflation target. Nick Rowe shows how well it worked:

The Bank of Canada does not have a crystal ball. But over the last few years its lack of a crystal ball didn’t seem to make much difference. Even with the benefit of hindsight, we can say that the Bank of Canada made almost no mistakes in doing what it needed to do to keep inflation on target.

The Bank of Canada kept inflation on target, almost exactly as it was supposed to.

And we know this wasn’t just luck, as Canadian inflation was much higher and more volatile during the earlier decades. Oddly, some economists insist it was luck, claiming that OMOs don’t do anything, as fiscal policy drives the price level.

Now Thornton obviously knows that central banks have successfully targeted gold prices, forex prices, and inflation. So presumably he means something different by “policy rules”. Indeed he goes on to discuss the Taylor rule, which is a very different sort of rule. It’s an “instrument rule,” a recipe for how policymakers should set the fed funds target, in order to hit their broader macro goals (inflation or NGDP.) And he’s right that no central bank has rigidly followed an instrument rule for interest rates, at least none that I know of.

But NGDPLT is not like the Taylor rule; it’s like inflation targeting. It’s a targeting rule. It sets the macro objective, not the interest rate path that is mostly likely to hit that objective. So why does he title his article as follows:

Is Nominal GDP Targeting a Rule Policymakers Could Accept?

In the final paragraph Thornton seems to realize that something was missing from his analysis, and tries to quickly patch things up:

The fact that monetary policy has been discretionary does not mean that policy rules and other basic economic relationships are useless. Indeed, they can be quite useful as guides to monetary policy decisionmaking. For example, it is useful to know whether the policy rate is consistent with the rate implied by the historical relationship given by a Taylor rule or, as I have suggested elsewhere, the Fisher equation.2 In the final analysis, however, policymakers will use discretion and not rules to conduct monetary policy.

Hence the title of my post. So rules such as inflation targeting can indeed be “quite useful as guides to monetary policy decisionmaking,” even if they don’t slavishly following a Taylor-style instrument rule in hitting the target. My claim is that we should replace inflation targeting as a “quite useful as guides to monetary policy decisionmaking” regime with NGDPLT as a “quite useful as guides to monetary policy decisionmaking” regime. Do what the Canadians did, except for NGDPLT.

PS. Thornton also makes the following odd claim:

So what prevents the Fed and other central banks from adopting nominal GDP targeting? Again, there are a number of reasons, but an important and sufficient reason is that nominal GDP targeting requires policymakers to be indifferent about the composition of nominal GDP growth between inflation and the growth of real output, and, in general, they are not. For example, let’s assume the target is 5 percent and nominal GDP is growing at 6 percent. Would policymakers react the same if the composition was 1 percent inflation and 5 percent real growth, or 5 percent inflation and 1 percent real growth? It seems unlikely.

That makes no sense to me, it would be like saying that a 2% inflation target means that policymakers should be indifferent between a situation with 1% service price inflation and 3% goods price inflation, versus a situation of 3% service price inflation and 1% goods price inflation. Yes, I suppose it would imply that, but why should we care? If Thornton has studied the NGDP targeting literature then he certainly knows why NGDPLT proponents say we should be indifferent between those two scenarios. But he never explains why that argument is wrong.

BTW, when commenters bring up the 1%/5% hypothetical, I am amused that they all insist the Fed would behave very differently in the two cases. But half insist the Fed would be tighter with the high inflation situation, and the other half vehemently insist just the opposite, that the Fed cares more about growth. So it’s far from obvious why these two situations would call for different Fed policy responses.

PPS. His article would have been greatly improved if he had keep in mind two concepts; changes in instrument rules necessitated by more information about the relationship between policy instruments and the macro targets (inflation, NGDP, etc), and changes in targeting rules necessitated by new information on the relationship between the macro aggregates and social welfare. This Bennett McCallum paper is a good introduction.

HT: RyGuy Sanchez, Keshav Srinivasan