1. Look how Newsweek puts things in perspective:

The bombardment was preceded by a large-scale Kurdish operation against Isis in northern Iraq, which saw 5,000 Kurdish fighters, supported by US-led coalition airstrikes, sweep around Mosul to recapture an area larger than the size of Andorra, Liechtenstein and San Marino combined.

That large, eh?

2. This surprised me:

Ms Schneider reckons that more than half of the world’s feed crops will soon be eaten by Chinese pigs.

And some more information:

As a result, land use is changing drastically on the other side of the world. In Brazil, more than 25m hectares of land—parts of which were once Amazon rainforest—are being used to cultivate soy (Chinese companies have not signed up to the “soy roundtable”, a voluntary association, the members of which agree not to buy soyabeans from newly deforested land). Entire species of plants and trees are being sacrificed to fatten China’s pigs. Argentina has chopped down thousands of hectares of forest and shifted its traditional cattle-breeding to remote areas to make way for soyabeans. Since 1990 the Argentine acreage given over to that crop has quadrupled: the country exports almost all of its whole soyabeans—around 8m tonnes—to China. In some areas farmers harvest two or three crops a year, using herbicides that have been linked to birth defects and increased cancer rates.

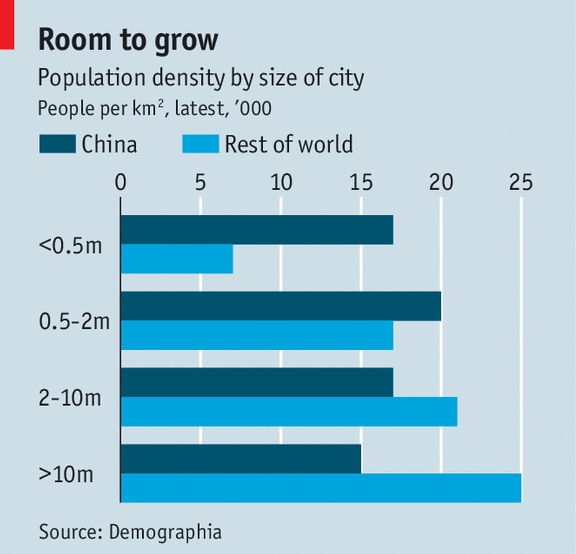

3. In China, small cities are more densely populated than large cities:

4. Here’s something you probably didn’t know about Edgar Allen Poe:

Poe’s mind was by no means commonplace. In the last year of his life he wrote a prose poem, Eureka, which would have established this fact beyond doubt—if it had not been so full of intuitive insight that neither his contemporaries nor subsequent generations, at least until the late twentieth century, could make any sense of it. Its very brilliance made it an object of ridicule, an instance of affectation and delusion, and so it is regarded to this day among readers and critics who are not at all abreast of contemporary physics. Eureka describes the origins of the universe in a single particle, from which “radiated” the atoms of which all matter is made. Minute dissimilarities of size and distribution among these atoms meant that the effects of gravity caused them to accumulate as matter, forming the physical universe.

This by itself would be a startling anticipation of modern cosmology, if Poe had not also drawn striking conclusions from it, for example that space and “duration” are one thing, that there might be stars that emit no light, that there is a repulsive force that in some degree counteracts the force of gravity, that there could be any number of universes with different laws simultaneous with ours, that our universe might collapse to its original state and another universe erupt from the particle it would have become, that our present universe may be one in a series.

All this is perfectly sound as observation, hypothesis, or speculation by the lights of science in the twenty-first century. And of course Poe had neither evidence nor authority for any of it. It was the product, he said, of a kind of aesthetic reasoning—therefore, he insisted, a poem. He was absolutely sincere about the truth of the account he had made of cosmic origins, and he was ridiculed for his sincerity. Eureka is important because it indicates the scale and the seriousness of Poe’s thinking, and its remarkable integrity. It demonstrates his use of his aesthetic sense as a particularly rigorous method of inquiry.

5. In a review of a book on disappearing religions, I found this:

In a Detroit supermarket Russell experiences one of the most moving moments in a book that is often tinged with sadness. As he roams the aisles, Russell notices voices speaking a language that echoes with the sounds of Arabic or Hebrew, though it is neither: it is Aramaic. “Amid the Muzak and synthetic fruit drinks in a suburban American store, I was hearing the language of Christ.” The people speaking it are Assyrian Christians from northern Iraq, the descendants of the legendary Church of the East. Its followers—some of whom (the Chaldeans) today answer to Rome—once claimed a tenth of all Christians among its flock. Their missionaries brought Christianity to China in 635. When Mel Gibson brought out his film version of the life of Christ, the Assyrians were among the few people in the world who could follow its Aramaic dialogue without the benefit of subtitles.

During the modern era, many Assyrian Christians settled in the city of Mosul, Iraq’s second largest. In June, the jihadist army that would soon rename itself “Islamic State” captured the city, setting off an exodus of Iraqi Christians that could well mean the end of yet another ancient religious presence in the Middle East. There are already more speakers of Aramaic in metropolitan Detroit (around a hundred thousand) than in Baghdad; the head of the Assyrian Christians, Patriarch Mar Dinkha IV, lives in Chicago. In the Midwest, they have their churches, clubs, restaurants, and newspapers. There is some comfort in the thought that they have found safety, and that in some degree their culture will endure. But this is small consolation for the loss of an entire world.

6. My favorite Indian film is The World of Apu (1959.) This story about an Indian bride who marries a wedding guest reminds me of the film.

7. Why is this called a “head transplant” and not a body transplant? And what does that say about our concept of personal identity?

8. This is rather surprising:

Britain has prized the ideal of economically mixed neighbourhoods since the 19th century. Poverty and disadvantage are intensified when poor people cluster, runs the argument; conversely, the rich are unfairly helped when they are surrounded by other rich people. Social mixing ought to help the poor. It sounds self-evident—and colours planning regulations that ensure much social and affordable housing is dotted among more expensive private homes. Yet “there is absolutely no serious evidence to support this,” says Paul Cheshire, a professor of economic geography at the London School of Economics (LSE).

And there is new evidence to suggest it is wrong. Researchers at Duke University in America followed over 1,600 children from age five to age 12 in England and Wales. They found that poor boys living in largely well-to-do neighbourhoods were the most likely to engage in anti-social behaviour, from lying and swearing to such petty misdemeanours as fighting, shoplifting and vandalism, according to a commonly used measure of problem behaviour. Misbehaviour starts very young (see chart 1) and intensifies as they grow older. Poor boys in the poorest neighbourhoods were the least likely to run into trouble. For rich kids, the opposite is true: those living in poor areas are more likely to misbehave.

9. Fight Islamic fundamentalism–put them in charge of the government:

Hardliners have long railed against “Westoxification” (the title of a book by Jalal Al-e Ahmad, published in 1962), yet in their daily lives they are now surrounded by Western consumer goods, computer games, beauty ideals, gender roles and many other influences. Iranian culture has not disappeared, but the traditional society envisaged by the fathers of the revolution is receding ever further.

The most visible shift is in public infrastructure. Tehran, the capital, is a tangle of new tunnels, bridges, overpasses, elevated roads and pedestrian walkways. Shiny towers rise in large numbers, despite the sanctions. Screens at bus stops display schedules in real time. Jack Straw, a former British foreign minister and a regular visitor, says that “Tehran looks and feels these days more like Madrid and Athens than Mumbai or Cairo.”

. . .

Iran is the modern world’s first and only constitutional theocracy. It is also one of the least religious countries in the Middle East. Islam plays a smaller role in public life today than it did a decade ago. The daughter of a high cleric contends that “religious belief is mostly gone. Faith has been replaced by disgust.” Whereas secular Arab leaders suppressed Islam for decades and thus created a rallying point for political grievances, in Iran the opposite happened.