One of the important tenets of market monetarism is that countries with their own currency can can control their nominal exchange rate. This means there is no such things as a “liquidity trap”; a country can simply depreciate its currency if it wishes to create inflation. Switzerland did this in 2011 and held the exchange rate at a depressed level for more than three years. But then the Swiss National Bank let the currency float higher, for reasons that still are not entirely clear. Some argued that they didn’t want to buy up so much foreign exchange, and that this somehow discredited the claim that a central bank could always depress its currency.

I doubted that explanation; the financial markets certainly didn’t see any reason why the Swiss would need to abandon the euro peg. Fortunately, another test case occurred at about the same time, in Denmark. Speculators bought lots of Danish krone and the central back was forced to buy lots of foreign assets to defend the currency. Here’s the FT from 5 months ago.

Denmark’s central bank governor pledged to face down speculators testing its currency peg to the euro, saying he would do “whatever it takes” to defend it.

Lars Rohde told the Financial Times that Nationalbank could “go on forever” defending the peg, after lowering interest rates four times in three weeks to a global record low of minus 0.75 per cent. It has also swelled its balance sheet to a record size by printing krone in an attempt to weaken the Danish currency.

“The main message is that we are ready to do whatever it takes to defend the peg. We have unlimited access to Danish krone and we have no restrictions on our balance sheet,” he said, in his first public comments since the recent quadruple rate cuts.

Tyler Cowen claimed this would provide a test of the claim that the Swiss were not forced to devalue:

I would bet against them, in any case this will be a neat test case for our judgments of Switzerland.

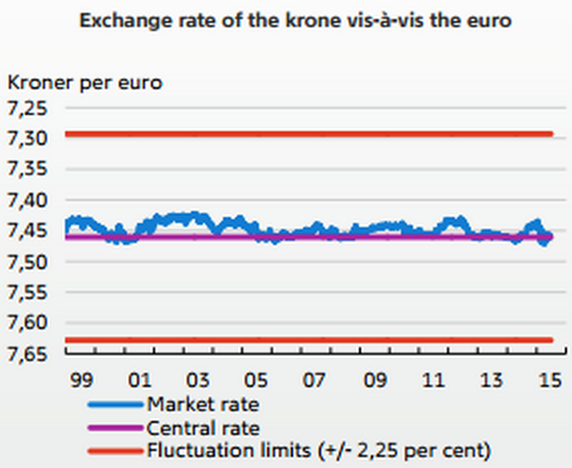

It’s not 100% clear what the test actually was. No one expected the Swiss to maintain their euro peg forever; it was always viewed as a temporary expedient. More likely, the test was whether the currency peg would be abandoned because of a wave of speculation anticipating a currency appreciation. If that’s the test, the Danes seemed to have passed:

It looks like the pressure is off, for now at least.

At the start of this year, it looked a bit like Denmark could be the new Switzerland, with some observers wondering whether the tiny Nordic nation could scrap its currency peg to the slumping euro.

Pressure ramped up quickly after the Swiss central bank nixed its cap on the franc, prompting a series of Danish interest rate cuts, writes Katie Martin.

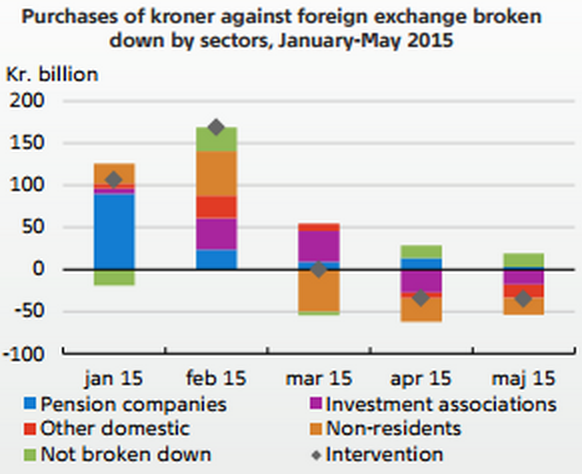

In its latest monetary review, Denmark’s central bank acknowledges that the market’s krone buying was enthusiastic in the opening months of the year.

The central bank is still intervening to lean against krone-positive flows. But it’s all on a much smaller scale.

It’s still not clear exactly why the SNB abandoned the peg (they gave mixed signals.) But if they left under “pressure” from speculators, it now looks like they made a serious mistake. It’s smooth sailing in Denmark:

And I might add that they defended their currency peg with strongly negative interest rates on reserves, an idea that was dismissed as impractical when I proposed it in early 2009. Some even claimed the policy would be contractionary. OK, so how has the krone not appreciated if negative IOR is contractionary? And why did the Swedish currency recently depreciate on news that IOR was being made even more negative?