This seemingly inexhaustible credit line is now drying up, with severely negative consequences for oil producers with debt that’s coming due.

Could the oil patch bust triggered by oil plummeting from $100/barrel to $50/barrel kick the U.S. into recession? Longtime correspondent B.C. recently observed: The question is whether the incipient recession in the energy and energy-related transport sectors is sufficient this time around to be the proximate cause of a US/global recession and real estate bust.

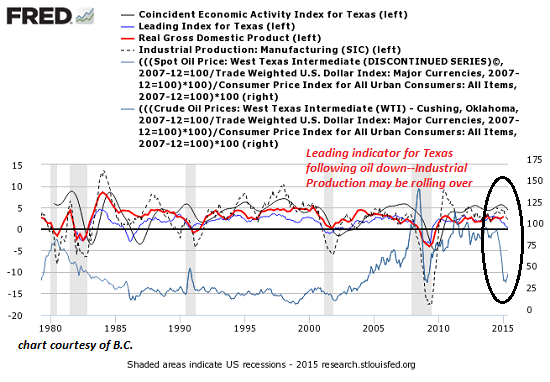

To help answer the question, B.C. sent this FRED chart of key measures of economic activity in Texas, America’s GDP and industrial production and the price of oil. The chart may look busy but the key indicators are oil (the blue line that fell off a cliff and has formed a fish hook), the red line (GDP adjusted for inflation, i.e. real GDP), the dotted line (industrial production) and the remaining two lines that reflect the leading indicators and economic activity in Texas.

Six months into the energy bust, the leading index for Texas has hit the zero line, U.S. industrial production has rolled over but real GDP hasn’t budged. So far, the impact of dramatically lower oil revenues has been limited to the oil patch, but the potential for contagion is still present.

As B.C. noted:

The last time the energy sector experienced a similar bust as is emerging today and clearly evident in Texas was in 1985-86, which occurred coincident with the crash in the price of oil and the onset of the S&L Crisis.

However, the US economy overall did not experience recession, but Industrial Production (manufacturing) decelerated to around 0% even as real GDP did not get close to “stall speed”, owing primarily to the effects of Baby Boomers entered the phase of life for peak spending and household formation.

Also, it did not hurt that the constant-US$ price of oil fell from $37 to $16 (similar scale as the recent drop from $100+ to $50/barrel) and the price of gasoline to below $2/gallon.

In other words, back in the 1980s oil bust, the drop in gasoline prices helped consumer spending and the mass entry of Baby Boomers into the housing market provided a source of broad-based economic stimulus.

The recent drop in gasoline prices has not stimulated consumer spending much, thwarting economists’ expectations of a big dividend from the oil bust.

Housing formation remains historically weak as home prices have soared out of reach of young families struggling with stagnant wages, crushing student loans and an uneven job market that rewards a few and leaves many with insecure incomes.

So these positives are either weak or missing in action.

But what’s different this time is the $550 billion that has been loaned to energy producers: Since early 2010, energy producers have raised $550 billion of new bonds and loans as the Federal Reserve held borrowing costs near zero, according to Deutsche Bank AG. With oil prices plunging, investors are questioning the ability of some issuers to meet their debt obligations. Research firm CreditSights Inc. predicts the default rate for energy junk bonds will double to eight percent next year.

This seemingly inexhaustible credit line is now drying up, with severely negative consequences for oil producers with debt that’s coming due and has to be rolled into new loans: Is The US Shale Industry About To Run Out Of Lifelines? (Zero Hedge).

Should oil resume its slide (and there are plentiful reasons this is likely–Saudi Arabia’s stated intention to increase market share, Iran’s plans to double its production and shale oil producers needing to maintain cash flow to make interest payments), then the well of ready credit could quickly dry up completely, pushing marginal producers and their lenders into insolvency.

What’s also different is a looming global recession, a $900 billion subprime auto-loan bubble that’s about to burst and an echo-bubble in housing that’s threatening to follow the first housing bubble’s trajectory of crash and burn.

The row of dominoes swaying unsteadily in these stiff winds won’t take much to topple.