[First a few notes. An increasing number of comments are getting diverted to spam, where I have to fish them out. But I won’t know this unless you tell me. Try leaving a short comment alerting me if your longer one didn’t take. No, I didn’t kill your comment because you disagree with me—never have. Also, I have a new post at Econlog discussing DeLong and Krugman on Friedman, and yesterday one on Andrew Sentance.]

When Abe took office I expected his policies to raise inflation and NGDP, but not as much as he hoped. I expected his policies to help the labor market, but cautioned that a fairly low unemployment rate and rapidly falling labor force would limit the gains in RGDP. I think I got all the big issues right, but missed on some of the components of RGDP.

Inflation figures have recently been whipsawed by both a big sales tax boost and then falling oil prices. Assuming oil prices don’t fall much further, then when the dust settles next year I expect inflation to be about 1%. But Abenomics has clearly raised the trend rate of inflation (which was negative under his predecessors.)

NGDP growth has not been all that impressive, until you compare it to NGDP over the previous 2 decades:

1994:1 495 trillion

2012:4 472 trillion -4.6%

2015:2 500 trillion +5.9%

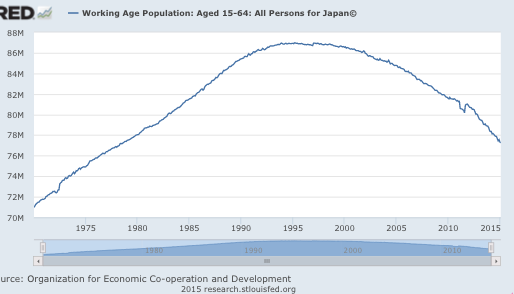

Without the sales tax increase last year, I’d guess NGDP would have been up about 4.0% to 5.0%. That’s a pretty slow rate of growth, less than 2%/year, but quite a turnaround from the previous 2 decades. Even more impressive, Abe took office just as the boomers were hitting retirement age. As a result the working age population is now falling much faster than during 1994-2012:

The working age population is now plunging at 1.4% per year. That fact alone makes the Japanese trend rate of RGDP growth about 2% lower than in the US, and the US trend rate is itself below 2%. (The Fed recently reduced their trend rate estimate to 2%; they’ll have to reduce it further in the future. BTW, with all of their talent it should not be possible for me to forecast which way they will miss, but I can do so, as can many others.)

The working age population is now plunging at 1.4% per year. That fact alone makes the Japanese trend rate of RGDP growth about 2% lower than in the US, and the US trend rate is itself below 2%. (The Fed recently reduced their trend rate estimate to 2%; they’ll have to reduce it further in the future. BTW, with all of their talent it should not be possible for me to forecast which way they will miss, but I can do so, as can many others.)

Any success I had predicting Japanese RGDP growth was dumb luck, as it reflected two offsetting factors that I missed:

1. Productivity has been horrible, worse than I expected

2. The labor force has been flat, despite the 1.4% annual decline in working age population. That’s better than I expected.

I suppose that second fact is mostly due to older Japanese working longer. Abe has also been trying to boost immigration, and female labor force participation. Perhaps that’s also played a role. (Immigrants are currently 1.1% of the workforce.)

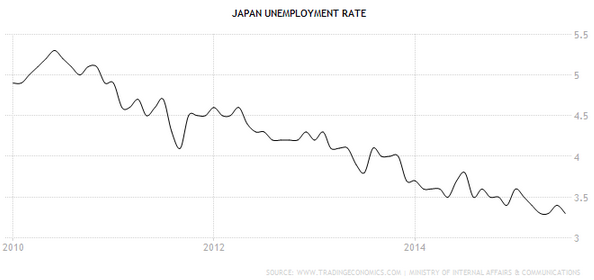

The unemployment rate has fallen to 3.3%, the lowest rate in 18 years.

Many Keynesians thought the big sales tax increase last year would be a mistake, but unemployment continued to decline and total employment rose. Another “austerity” prediction gone wrong. (Is anyone still keeping track of these failures? I’ve lost count.) The so-called “recession” of 2014 consisted of Japanese shoppers splurging in March to beat the April 1 tax increase, and then cutting back after the tax increase. Some Keynesians actually claimed that that showed fiscal policy matters.

Back when Japan had a higher unemployment rate, I emphasized that monetary stimulus could boost growth. Now with low unemployment and a falling population, I think the strongest argument for faster NGDP growth is their huge public debt.

If the number of 15-64 year olds had remained constant since 1991, Japan’s GDP would now be more than 8% higher (see figure 8).

Demographic decline was not, however, anything like the biggest drag on nominal GDP. That honor belongs to Japan’s stubborn deflation. If prices had remained flat since 1991, Japan’s nominal GDP would now be 20% higher. If prices had instead risen by 2% a year, consistent with international norms of price stability, nominal GDP would be over 80% bigger.

An 80% bigger NGDP would have meant a big fall in the public debt/GDP ratio, even accounting for the fact that nominal interest rates (and hence budget deficits) might have been a bit higher. Also recall, however, that faster NGDP growth would have meant at least slightly stronger RGDP growth, and also fewer wasteful Japanese fiscal projects such as bridges to nowhere. Both of those factors would have reduced the deficit.

Why have Abe’s policies been viewed as a mixed bag? Partly because the third arrow of supply side reforms haven’t had much effect, and hence real wages are still very weak. And while the sales tax increase is fiscally responsible, and necessary (since they can’t seem to cut spending), it’s obviously also painful.