Britonomist recently left this comment, in response to my claim that the demand for cash is negatively related to the market interest rate (and the demand for reserves is negatively related to the market interest rate minus IOR):

Do you mean cash here? I think for almost everyone the demand for cash is extremely inelastic in a modern economy. Lowering interest rates won’t cause people to rush to their bank account to withdraw money.

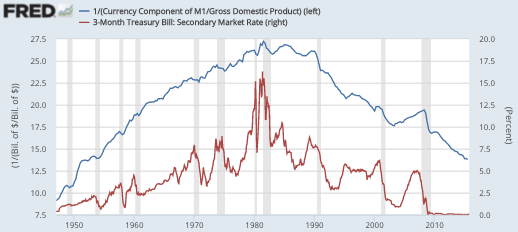

Classic error, often made by people on the left. There’s a tendency to underestimate the degree to which people respond to incentives. Interest rates are the opportunity cost of holding cash. If you lower interest rates, people will choose to hold more cash. And yes, that means lower interest rates are contractionary, as I said in a number of recent posts. Here’s a graph showing the relationship between the demand for currency (as a share of GDP) and T-bill yields:

Notice that the two variables tend to move inversely. After 2008, the yield on T-bills fell close to zero, and the demand for cash soared from just over 5% of GDP to just over 7%. Today’s currency demand is about 40% larger than it would be had interest rates stayed at the levels of 2007.

Over the previous several decades, interest rates had been trending downwards from their 1981 high point, while the demand for currency had been trending upward from its 1981 low point. Prior to 1981, interest rates had trended upwards for many decades, while currency demand had trended downwards.

This isn’t to say that the two variables are perfectly (negatively) correlated. Other factors such as tax rates also impact currency demand. And it is costly for currency hoarders to quickly adjust their stocks of currency, as most currency demand is for things like tax avoidance. Thus the stock demand for currency responds gradually to changes in the opportunity cost of holding currency. It’s a much smoother time series.

To summarize:

1. The business cycle in the US is mostly caused by fluctuations in NGDP.

2. Fluctuations in NGDP are mostly caused by changes in interest rates, which impact base velocity. Lower interest rates reduce base velocity, causing NGDP to decline, and if wages are sticky (and they are), also causing RGDP to decline. Ironically the lower interest rates that cause recessions are themselves often caused by a failure to cut rates quickly enough in the face of a drop in the Wicksellian rate.

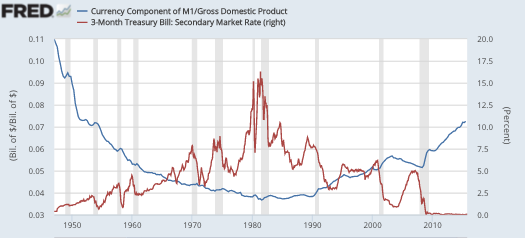

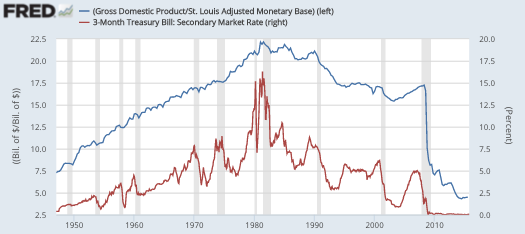

Higher interest rates tend to raise base velocity, causing NGDP and RGDP to rise. Of course changes in the base also influence NGDP; but as a practical matter changes in velocity are usually more important. The graph below inverts Cash/GDP, to give us cash velocity against interest rates:

Those drops in cash velocity during the recessions (grey bands) are lower rates causing currency hoarding causing recessions. And the last graph replaces currency with the monetary base, which is obviously distorted once the program of IOR began:

Whenever I claim that low interest rates cause recessions, I get misunderstood. So let me try to clarify the remark, while explaining why both the Keynesians and the NeoFisherians are wrong.

Whenever I claim that low interest rates cause recessions, I get misunderstood. So let me try to clarify the remark, while explaining why both the Keynesians and the NeoFisherians are wrong.

The Keynesians would say that the counterfactual policy that would prevent recessions is even lower interest rates. That’s mostly wrong. The proper counterfactual policy to prevent recessions would actually lead to higher interest rates, on average, during the formerly recessionary period, which is no longer a recession. Keynesians would also say that low rates don’t cause recessions, recessions cause low rates. I get that, but what they don’t get is that there really is causation from lower rates to lower base money velocity to recessions. That’s because they tend to ignore M and V, and think in terms of false non-monetary models of “spending”. (Barsky and Summers understood the point I’m making.)

But the NeoFisherians are wrong in assuming that the proper instruction to central banks is “higher interest rates to prevent deflation”. That’s because central banks interpret that command as “raise rates via the liquidity effect from a contractionary monetary policy”, which is deflationary.

Much of macro is balancing two seemingly incompatible ideas in your mind at the same time. For instance, printing money doesn’t create growth and printing money does create growth. Both ideas are true (or false), in the right context. The same is true of interest rates. There’s a sense in which lower rates are contractionary, and another sense in which they are expansionary. Only a few economists (notably Nick Rowe) seem able to get the proper balance right, for these two seemingly incompatible ideas.