Once upon a time, falling interest rates were great for banks. A lower cost of capital gave lenders access to cheap raw material while causing borrowers to clamber for what banks were selling. Large profits usually ensued.

But not now. Rates have fallen past the banks’ sweet spot to levels that just don’t work. Borrowers appear to be spooked rather than energized and trading desks are imploding amid “catastrophic volatility“. See German bond yields collapse below 50bps for first time ever and UBS’s investment bank earnings decline 63% on equities trading.

And now yield curves are inverting — that is, long rates are falling below short rates, which means banks’ borrowing costs (the short end of the yield curve) are starting exceed their lending revenue (the long end of the curve). See Japan’s yield curve faces further pounding amid BoJ aftershock and US Treasury yield curve inverts.

To add a little spice to the toxic stew, capital controls are coming back into style:

Germany proposes new cash ban and capital controls as Europe rushes towards NIRP

(Examiner) – Last Friday, Japan was the first major economy to cross the ‘Rubicon’ by implementing negative interest rates (NIRP) in an attempt to force their people to spend, and slow deflation as the 3rd largest economy moves into recession. However, in this Japan is not an island, with several other nations already preparing to do the same to protect their diminishing economies.

And in all of this there is one surprising country that appears to also be preparing for NIRP as on Feb. 3, coalition group of German legislators introduced a bill to limit the use of cash, and to ban the use of the 500 Euro bill in personal and non-bank transactions.

The significance of this is that when a central bank implements policies that make holding your money in a bank a liability, then the natural recourse is for depositors and account holders to simply take it out and move their wealth into assets that are either outside their nation’s currency, or into commodities such as gold and silver which provide no benefit to an economy that desperately needs its people to spend and create inflation and growth.

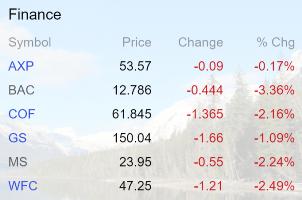

Not surprisingly, US bank stocks are getting whacked. As of 9am on Wednesday Feb 3:

Bank of America (BAC) stands out as especially cringe-worthy, having fallen from north of $18 per share to below $13 in just a few weeks:

What does all this mean? The broad-strokes answer is that these huge, nearly-omnipotent entities that have dominated and defined the world’s economic and political landscape may finally be receding towards a more reasonable level of power. One way to gauge this is by the rhetoric coming out of the current presidential candidates, all of whom have decided that it’s not just safe, but profitable to bash Wall Street. Dimon, Blankfein, et al are clearly not the bullies they once were.

More immediately it means there’s a new black swan in the sky. As a group the world’s biggest banks are leveraged to an extent that probably has the authors of the Glass-Steagall Act spinning in their graves. The notional value of their over-the-counter derivatives books dwarfs the global economy, while their exposure to now-moribund sections of the oil and gas industry guarantees massive write-offs in the year ahead. The question isn’t whether the big banks will report huge losses, but whether one of them will be destroyed in the process, giving us another Lehman Moment.