It was always a matter of when, not if, the financial markets would tell the Fed to stop raising interest rates. And it appears the message has been received:

Fed’s Bullard speaks against further interest-rate hikes

(MarketWatch) — A Federal Reserve official who was one of the strongest advocates of raising rates last year now believes the central bank should refrain from further boosts in borrowing costs for now.

In a speech in St. Louis on Wednesday, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis President James Bullard said declining interest expectations and declines in financial markets argue against further boosts in the central bank’s short-term interest rate target, which now rests at a range of 0.25% to 0.50%.

“Two important pillars of the 2015 case for U.S. monetary policy normalization have changed,” Bullard said. “These data-dependent changes likely give the [Federal Open Market Committee] more leeway in its normalization program,” he said in reference to central bankers’ plans to raise rates further this year.

“Inflation expectations have fallen further,” and with the losses seen in markets, “the risk of asset price bubbles over the medium term appears to have diminished,” he said. That takes pressure off the Fed relative to last year, when the price outlook and high asset prices pointed to a need for higher rates, the official said.

Bullard spoke in the wake of the release of meeting minutes from the Fed’s January policy meeting. Having boosted rates in December the Fed refrained from action last month. The minutes showed policy makers were struggling to come to terms with why markets were performing so badly against a relatively sound U.S. economic outlook.

So much good stuff here.

“Policy makers were struggling to come to terms with why markets were performing so badly against a relatively sound U.S. economic outlook.” Apparently the highly-trained professionals at the Fed, when gauging the health of the economy, overlooked collapsing commodity prices, a shrinking manufacturing sector and soaring levels of student and auto debt, and saw only the fictitious headline unemployment number.

The reason for this apparent blind spot goes right to the heart of the Keynesian/Austrian debate: The former (who populate government and academia) don’t include debt in their models, and so tend to view any kind of consumption or jobs growth as unambiguously good regardless of how much borrowing is necessary to achieve it. So rising sub-prime auto loans, for instance, are a healthy sign because they signal more people buying more stuff.

Austrians, in contrast, focus on society’s balance sheet and view soaring leverage — especially for things of questionable value like cars and many college degrees — as a potential problem. Guess who is always right at big turning points?

Other data points that have been screaming “don’t raise rates” include:

Margin debt — created when investors borrow against their stocks to buy more stocks — soared to a new record in 2014. For mainstream economists this was fine because it meant people were optimistic and willing to both speculate and — due to the wealth effect of rising equity prices — buy more houses, TVs and SUVs. Austrians would simply note what happened the previous two times investors leveraged themselves to the hilt and assume that a reversal is imminent.

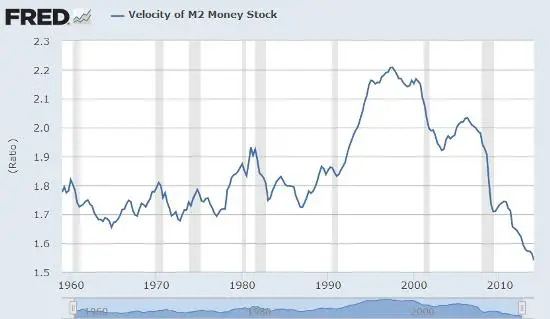

The velocity of money — the rate at which dollars, once created, are spent — has been plunging as debt has been soaring. To mainstream economists, this is “puzzling.” To Austrian economists it’s obvious that if you borrow too much money you’ll spend less in the future because you’re either unwilling or unable to borrow more.

One final illustration of Fed cluelessness is the idea that plunging commodity prices boost the economy by putting money into consumers’ pockets. See Janet Yellen: Cheap oil is good for America.

Here again, this ignores the related leverage. Several trillion dollars have been borrowed via bank loans and junk bonds to fund a vast expansion of US oil and gas drilling capacity. Should a big part of that debt default — which now looks certain — the impact will more than offset cheaper gas. See Commodities’ $3.6 trillion black hole.

We could do this all day. For almost every aspect of the modern global economy, the people pulling the levers seem to be ignoring the single biggest indicator of systemic health, which is the balance sheet. So the Fed, ECB, Bank of Japan, Congressional Budget Office, and most university economics departments will continue to be surprised by what happens and will, as a result, keep doing the wrong thing.

Now, if raising interest rates was a dumb thing for the Fed to do, does that mean cutting interest rates would be smart? No! The lesson to be drawn from today’s mess is that the way to avoid a debt-driven crisis is to avoid borrowing too much in the first place. Once a society is sufficiently over-leveraged there’s really nothing it can do but let the inevitable bust happen and resolve to do better next time.