Yesterday Japan’s government borrowed money on terms that require the lenders to pay rather than receive interest for ten years. And not only was that bond issue snapped up, it was vastly oversubscribed. This raises a lot of questions, the chief being “why would anyone voluntarily commit to something that’s guaranteed to lose money for a decade?”

The short, obvious answer is that the world’s central banks are creating so much excess cash that there seems to be nowhere else for it to go. The longer, but way more interesting and scary explanation is that capitalism as it used to function is over, and the result will be catastrophic.

Here’s an overview of those Japanese bonds:

Japan Sells 10-Year Bonds at Negative Yield For the First Time

(Bloomberg) – The Japanese government got paid to borrow money for a decade for the first time, selling 2.2 trillion yen ($19.5 billion) of the debt at an average yield of minus 0.024 percent on Tuesday.

The sale drew bids for 3.2 times the amount of the securities offered, the first increase in demand since an auction in December, according to the Finance Ministry. Japanese government bonds of as long as five years in maturity sold at an average yield below zero for the first time last month, after the Bank of Japan pushed yields lower across the curve with the announcement of negative interest rates Jan. 29.

“Demand was stronger than expected,” said Shuichi Ohsaki, chief rates strategist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch. “The outcome suggests there is ample demand before redemption of existing bonds in March.”

The benchmark 10-year bond yield dropped as low as minus 0.075 percent after the auction, matching a record. Yields on 20-year debt sank to an unprecedented 0.46 percent, while those on 30-year securities declined to an all-time low of 0.765 percent.

The JGB yield curve was the flattest on record at the end of last week, under pressure from the BOJ’s bond purchases, with the premium offered by 10-year securities over two-year notes narrowing to just 11.5 basis points.

The central bank buys as much as 12 trillion yen of the nation’s government debt a month.

And here’s bond fund manager Bill Gross’ take on flattening yield curves:

Bill Gross: Flat Yield Curve Crushes Capitalism

(ThinkAdvisor) – For most of 2015, famed bond investor Bill Gross has been railing against the Federal Reserve’s zero interest rate policy, urging the Fed to raise short-term interest rates because current low rates are stalling economic growth and short-changing savers.

“Capitalism does not function well, and profit growth is stunted, if short-term and long-term yields near the zero bound are low and the yield curve inappropriately flat,” writes Gross, who manages the Janus Global Unconstrained Bond Fund.

Gross explains that a flattening yield curve, with rates near zero, and the expectation of continued low rates reduce bank profit margin, corporate profits and any incentive to invest long term.

“It would seem that lower borrowing costs in historical logic should cause companies and households to borrow and spend more,” writes Gross. “The post-Lehman experience, as well as the lost decades of Japan, however, show that they may not, if these longer term yields are close to the zero bound.”

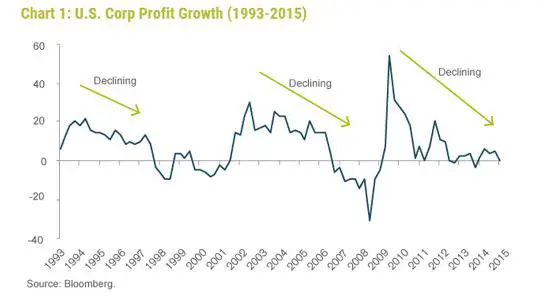

Gross includes a chart showing that U.S. corporate profits, between 1993 and 2015, declined during periods of falling interest rates:

He adds that a flattening curve with rates near zero also slows returns on investments for insurance companies and pension funds, which could further squeeze corporate profits as companies with defined benefit plans are forced to increase contributions.

Some thoughts

The crucial sentence from the Bloomberg article is “The central bank buys as much as 12 trillion yen of the nation’s government debt a month.” That means, in effect, that Japan’s central bank is directly funding its government, something once widely understood to be the last gasp of a dying regime but now seen as just part of the new normal.

Gross’ thoughts on the impact of negative rates on huge swaths of the finance industry are also key. Life insurance companies, for instance, take in premiums today and invest them to be able to cover their obligations when policyholders eventually die. They price their policies on the assumption of a mid-single digit positive return on their bond portfolios. Turn that return negative and all of a sudden the world’s life insurers are either unprofitable or insolvent. And that’s a big industry.

Pension funds, meanwhile, operate the same way, taking in and investing contributions against future obligations. Many US pension plans are already borderline broke and in a NIRP environment they’ll suffer a mass extinction. Again, big industry, many employees, huge potential impact on both Wall Street and Main Street.

The slowing growth that results from negative interest rates is thus profoundly deflationary, which presents another explanation for investors’ willingness to park cash in places that cost rather than generate income: They expect the currency they get back to be worth more than the currency they put in.

This is exactly the opposite of what rate-cutting central banks are hoping for — which might in the end be the moral of this tale: Economic laws are like their natural counterparts. You mess with them at your peril.