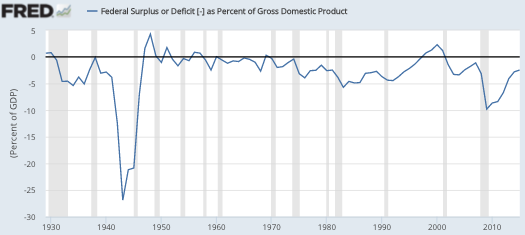

As I get older, I become increasingly interested in the mythological folktales that are believed by most economists. For instance the idea that LBJ refused to pay for his guns and butter program, ran big deficits, and kicked off the Great Inflation. All you need to do is spend 2 minutes checking deficit data on FRED to know that this is a complete myth, but apparently most economists just can’t be bothered.

During the 1960s, the budget deficit exceeded 1.2% of GDP only once, in fiscal 1968 (mid-1967 to mid-1968. LBJ responded with sharp tax increases in 1968, and the deficit immediately went away.

During the 1960s, the budget deficit exceeded 1.2% of GDP only once, in fiscal 1968 (mid-1967 to mid-1968. LBJ responded with sharp tax increases in 1968, and the deficit immediately went away.

The LBJ guns, butter and deficits story is too good to drop now, it’s in all the textbooks. It would be like admitting that the textbooks were wrong when they tell students that the classical economists believed that money was neutral and that wages and prices were flexible. We can’t do that, it’s too confusing.

Another one I love is that monetary policy impacts the economy with “long and variable lags”.

I’ve talked about this before, but today I have a bit more evidence. The idea that monetary policy affects RGDP with long and variable lags has three components, one or more of which must be true for the theory to hold:

1. Monetary policy affects NGDP expectations with a long and variable lag.

2. Changes in NGDP expectations affect actual NGDP with a long and variable lag.

3. Changes in actual NGDP affect actual RGDP with a long and variable lag.

All three are false. The third claim is obviously false; NGDP and RGDP tend to move together over the business cycle. So the entire theory of long and variable lags boils down to the relationship between monetary policy and NGDP.

The first claim is also obviously false, as it would imply a gross failure of the EMH. Now the EMH is clearly not precisely true, but it’s also obvious that market expectations respond immediately to important news events. Even EMH critics like Robert Shiller don’t claim that an earnings shock hits stocks two week later; it hits stock prices within milliseconds of the announcement. That part of the EMH is rock solid. There is no lag between policy shocks and changes in expectations of future NGDP growth.

So the entire long and variable lags theory rests on the second claim, that NGDP responds with a lag to changes in future expected NGDP. Unlike the first and third claim, that’s possible. But it’s also highly, highly unlikely. While we don’t have an NGDP futures market, the markets we do have strongly suggest that markets (and hence expectations) move with the business cycle, not ahead of the cycle.

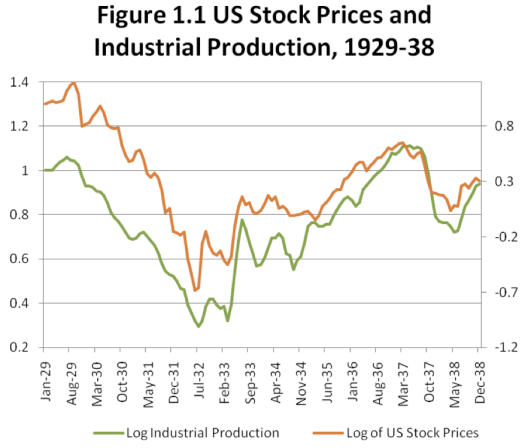

Perhaps the best period to test this theory is the 1930s. That decade saw massive RGDP and NGDP instability, which was clearly linked to asset price changes. Put simply, the Great Depression devastated the stock market. Here’s the correlation between stock prices and industrial production, from my new book:

The stock market is clearly not a leading or lagging indicator; it’s a coincident indicator. And that’s not just true in the 1930s; it’s also true today:

The stock market is clearly not a leading or lagging indicator; it’s a coincident indicator. And that’s not just true in the 1930s; it’s also true today:

The onset of the recession lines up, as does the steep part of the recession. The stock recovery in 2009 did lead by a few months, but the recent slump in IP led stocks by a few months. In any case, there are no long and variable lags; it’s basically a roughly coincident indicator when there are massive changes in NGDP.

The onset of the recession lines up, as does the steep part of the recession. The stock recovery in 2009 did lead by a few months, but the recent slump in IP led stocks by a few months. In any case, there are no long and variable lags; it’s basically a roughly coincident indicator when there are massive changes in NGDP.

If there actually were long and variable lags between changes in expected NGDP and changes in actual NGDP (and RGDP), then forecasters would be able to at least occasionally forecast the business cycle. But they cannot. A recent study showed that the IMF failed to predict 220 of the past 220 periods of negative growth in its members. That sounds horrible, but in a strange way it’s sort of reassuring.

Suppose that the business cycle is random, unforecastable, as I claim. And suppose that declines in GDP occurred one out of every five years. In that case, the rational forecast would always be growth. As an analogy, if I were asked to forecast a “green outcome” in roulette, I never would. Each spin of the wheel I’d forecast red or black. I’d end up forecasting 220 consecutive “non-greens” outcomes. And yet, there would probably end up being about 11 0r 12 green outcomes during that period, and I’d miss all of them. A 100% failure to predict greens. Because I’m smart.

Of course if there really were long and variable lags, say 6 to 18 months, then there would be occasions where the IMF would notice extremely contractionary monetary policy, and accurately predict recessions. I’m not saying they’d always be accurate. The lags are “variable” (a copout to cover up the dirty little secret that there are no lags, just as astrologers cover their failures with the excuse that their model is complicated, and doesn’t always work.) No, they would not always be successful, but they’d nail at least some of those 220 recessions. But they predicted none of them. And that’s because there are no lags. Because recessions begin immediately after the thing that causes recessions happens.

That’s the message the markets are sending loud and clear. But economists can’t be bothered; they have their comforting stories. Who can forget this line from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance:

Ranson Stoddard: You’re not going to use the story, Mr. Scott?

Maxwell Scott: No, sir. This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.