China is a glass half full country, and will be for the foreseeable future. Here I’ll point out what’s wrong with the China bulls and bears. Let’s start with the bears.

Last year lots of China bears predicted recession, after the stock market crashed and the yuan fell in a disorderly fashion in forex markets. The recession did not happen. In recent years, lots of people have pointed to “ghost cities” in China. According to this article, the ghost cities are filling up quite nicely:

Lingang was built for one reason: to support the new Yangshan deep sea port and corresponding FTZ, which link into the new city’s southern edge, as well as the nearby Lingang Industrial Zone. 800,000 people were projected to be living there by 2020, and the phrase “mini Hong Kong” was often uttered to describe what it was meant to become.

Construction on the $5.6 billion, 133 square kilometer satellite city began in 2003, but ten years later the place was a virtual ghost town. While I was told at that time that the emerging city had 50,000 residents, its wide open, empty streets and completely vacant housing blocks indicated that this may have been a wishful overestimate. While every property that went on the market there sold quickly, home buyers were hesitant to move in — who is going to move into a city before it’s ready to be inhabited?On one of my early visits to Lingang in 2013 I met with a team of researchers from Colliers who were scouting out a location for an impending hotel for a client. They weren’t put off by the excessive amount of empty buildings.

“It has potential,” Marco Zhou, the leader of the team, said as we looked out over an expanse of vacant construction lots and a yet-to-be-used high-tech park.

“Who do you think will come to this hotel?” I queried skeptically. “There really isn’t much going on here.”

“Don’t worry, man, all that will change,” Zhou replied with a laugh. “It is just a matter of time. They will all be filled . . . The only question here is when.”

This sentiment was echoed by the fact that a couple of days before two nearby plots of land sold for record prices, going for 445.45% and 427.4% premiums respectively.

Sounds like a typical ghost city, right? Here’s a return visit, two years later:

Since the last time I was in Lingang, Shanghai’s Free Trade Zones had been officially commissioned and its administrative offices moved in, the deep sea port continued expanding, the high-tech park began welcoming businesses, some of the office complexes had opened, the 100,000 student university town continued developing, and a new metro line linking in the new city to the core of Shanghai went into operation.

While not yet running at 100% capacity, considerable progress had been made. There was a steady stream of cars on the main road where there wasn’t any sign of traffic before, workers were walking in an out of previously unused office towers, a slew of new restaurants had opened, and many once-uninhabited residential complexes had filled up. The new city that had once been the domain of exiled students and migrant construction workers was now home to actual residents, white collar workers, researchers and shoppers.

“It’s full of life,” the news anchor complained. “It just looks like normal.” . . .

China seldom builds colossal new cities without a broader, larger-scale development plan. The ghost city narrative of cities built for nobody doesn’t stand up if you look at how many of the country’s booming new metropolitan areas were once mocked as being ghost towns.

New city building is obviously a long-term endeavor — long-term meaning 15 or 20 years, not five or six. Nearly all of China’s major “ghost cities” have by now filled up or are on pace to meet their population goals, giving the phrase “too big to fail” real-life relevance:

Shanghai’s Pudong financial center can no longer be considered a “statist monument for a dead pharaoh on the level of the pyramids;” Zhengdong New District is now the million person plus financial capital of Henan province rather than being “uninhabited for miles and miles and miles;” and even the “Great Ghost Mall of China” has come back from the dead.

The reason why China never gives up on its ghost cities is that they tend to eventually work.

And now for the bulls. This article claims that China (and India) is booming because of lots of state investment:

Why Are China and India Growing So Fast? State Investment

. . . In 2015 China’s per capita GDP growth was 6.4 percent and India’s 6.3 percent based on World Bank data.

These are easily the fastest growth rates for any major economies. They also propel the most rapid rates of growth of household and total consumption. In particular, both China and India are growing far more rapidly than the Western economies — in 2015 the EU’s per capita was only 1.7 percent, the U.S. 1.6 percent, and Japan’s 0.6 percent. Data for 2016 to date show the same pattern of rapid growth in China and India and slow growth in the U.S., EU and Japan.

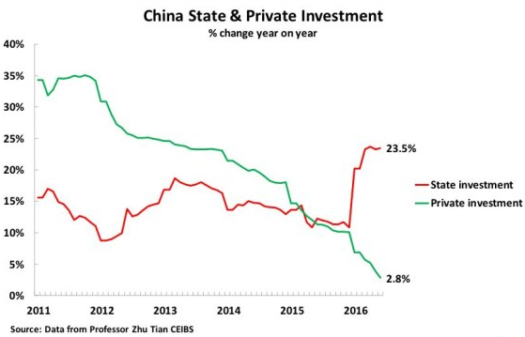

Professor Zhu Tian from China Europe International Business School points out, referring to National Statistics Bureau data, that from January to June 2016, state-owned fixed-asset investment had grown by 23.5 percent over the same period last year, but private fixed asset investment growth had decelerated to 2.8 percent.

Put aside the fact that China and India grow faster than Western economies because of catch-up growth. This graph shows almost exactly the opposite of what the author claims. Until 2015, private investment was growing faster than state investment. And during this period, China grew rapidly. As the gap narrowed, and then reversed, China’s growth slowed. The author’s argument is basically that China is still growing pretty fast in 2016, and its state is investing a lot in 2016. That’s it.

Put aside the fact that China and India grow faster than Western economies because of catch-up growth. This graph shows almost exactly the opposite of what the author claims. Until 2015, private investment was growing faster than state investment. And during this period, China grew rapidly. As the gap narrowed, and then reversed, China’s growth slowed. The author’s argument is basically that China is still growing pretty fast in 2016, and its state is investing a lot in 2016. That’s it.

In fact, this graph is almost exactly what you’d expect if state led investment did not boost growth, but instead simply crowded out private investment. The truth is that China’s grow surge began in 1979, when they started to allow private enterprise, and the state sector is a net drag on growth.

Now in fairness, China’s state does build infrastructure more efficiently than most other countries. In fact, the author’s attempt to lump together China and India make no sense, as India’s government is notoriously inept at building infrastructure. So why is India growing faster than China? Because it’s poorer, so the “catch-up growth” factor is more powerful. When China was as poor as India currently is, it was growing at double-digit rates.

The author claims that these Asian miracles provide justification for more state investment in the US. If our government was willing to build infrastructure cheaply, as Singapore and Dubai do, then I’d be all for more state investment in infrastructure (although even in that case I’d prefer private investment, like the recent passenger rail project being built in Florida, or Hong Kong’s private subway system.) But the US is not willing to build infrastructure cheaply, and hence any new projects are likely to be California high-speed rail-style boondoggles.

PS. No time for comments today, as I’ll be traveling. I really enjoyed yesterday’s Mercatus/Cato conference on monetary rules. John Taylor gave the keynote address, and I had a chance to meet interesting people like Miles Kimball and Peter Ireland.