Rajat asked one of his characteristically probing questions, in the previous post:

As you’ve often said with monetary policy, it all depends on the yardstick or counterfactual. With your examples, because you’ve put the focus on interest rates, the reader naturally assumes that the counterfactual is no change in official interest rates. For example, in (1), surely the cut in the Fed Funds rate from 5.25% to 2% was less contractionary than if the Fed did not lower the rate? The money supply may not have risen in 2007-08, but wouldn’t it have fallen if rates were kept at 5.25%, as the market devoured the short-term securities the Fed offered at that yield? I understand that the reduction in official rates was not expansionary in any meaningful sense (ie against a benchmark of ideal monetary policy under inflation or NGDP targeting).

This is probably correct, but I’d argue that it could also be misleading, resulting in too much reassurance that interest rates aren’t that bad an indicator after all. Rajat’s point is that if the Fed never even began cutting rates, then they would have had to reduce the money supply rather dramatically. So much so that NGDP would have done even worse than with cut from 5.25% to 2.0%. So does that mean the interest rate cut was expansionary after all? Not quite.

Consider the two following hypotheticals:

A. No change in the base from August 2007 to May 2008, rates fall from 5.25% to 2.0% (actual policy)

B. The base rises by 5%, while rates move from 5.25% in August 2007 to 5.25% in May 2008.

I would claim that policy B is almost certainly more expansionary. Rajat might reply that policy B was not an option. If the monetary base had risen by 5%, then interest rates would have declined even more rapidly than they actually did.

I don’t quite agree, although for any given day I’d agree with that claim. Thus on any given day, a lower fed funds target requires a larger base than otherwise (at least before IOR was instituted in October 2008). But that true fact leads many Keynesians to jump to a seemingly similar, but unjustified conclusion. Many people assume that over a 9-month period a more expansionary monetary policy implies a faster decline in interest rates.

In fact, option B probably was available to the Fed, but only if they moved much more aggressively in the early part of this period and/or if they changed their policy target. Thus there are two possible ways the Fed might have achieved policy option B:

B1. Cut rates sharply enough in August 2007 to dramatically boost NGDP growth expectations, and then gradually raise rates enough over the next few months to get them back to 5.25% by May 2008. In that case, NGDP growth would have held up well, and yet the path of interest rates over that period would have ended up higher than otherwise.

B2. Adopt a policy of 5% NGDPLT, which would have radically changed expectations, and hence boosted the Wicksellian equilibrium rate.

Rajat might view option B2 as cheating, so let me make a case for option B1. I’d argue that the Fed did almost exactly what I describe in option B1 during 1967. Just to set the scene, the economy was slowing sharply during early 1967, and some people worried that we might enter a recession. The Fed moved quite aggressively, and their move was so successful that over a period of 10 months there was no rate cut at all.

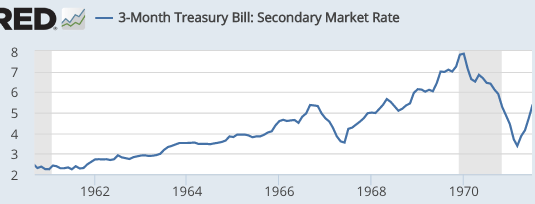

3 month T-bill yields:

January 1967: 4.72%

June 1967: 3.54%

November 1967: 4.73%

So interest rates were basically unchanged over this period, and yet I’d argue that policy was far more expansionary than during August 2007 to May 2008, when rates fell sharply. The monetary base grew by over 5% in just 10 months, and this allowed the US to avoid recession.

(BTW, in retrospect, a mild recession would have been preferable in 1967, as a way of avoiding the Great Inflation. Instead, the US left the gold standard in April 1968, Bretton Woods blew up 3 years later, and the rest is history. But since policymakers didn’t know all of this would occur, the mistake of the 1960s was sort of inevitable—just a question of when.)

In 1967, the expansionary policy early in the year boosted NGDP growth expectations enough so that they could raise rates back up later in the year, and still see robust NGDP growth. In 1968, interest rates rose still higher, but this was expansionary because the base was also rising briskly. So you have both rising base velocity (from higher rates) and a rising monetary base.

There’s a grain of truth in Rajat’s comment, but it’s best thought of as applying to a given day, where a lower interest rate implies a faster growth in the money supply, and easier money. Over a more extended period of time things become much dicier. Those who focus on interest rates are more likely to be led astray, the longer the period being examined.