Over at Econlog I have a post that suggests the answer is no, CA deficits do not cost jobs.

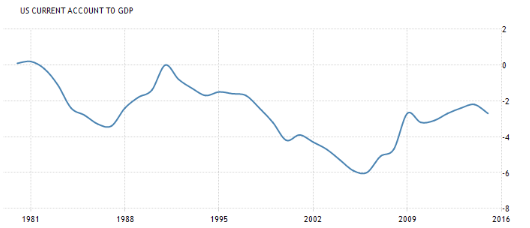

But suppose I’m wrong, and suppose they do cost jobs. In that case, trade has been a major net contributor to American jobs during the 21st century, as our deficit was about 4% of GDP during the 2000 tech boom, and as large as 6% of GDP during the 2006 housing boom. Today it is only 2.6% of GDP. So if you really believe that rising trade deficits cost jobs, you’d be forced to believe that the shrinking deficits since 2000 have created jobs.

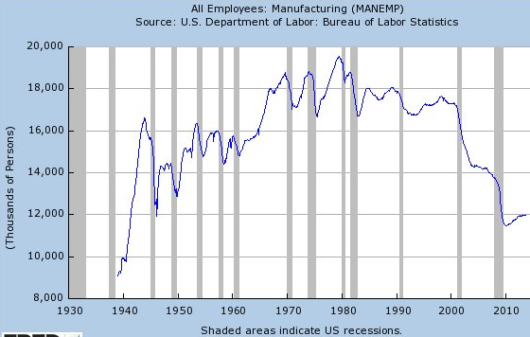

So why have manufacturing jobs plummeted since 2000? One answer is that the current account deficit is the wrong figure, since it also includes our surplus in trade in services. If you just look at goods, the deficit is closer to 4.2% of GDP.

So why have manufacturing jobs plummeted since 2000? One answer is that the current account deficit is the wrong figure, since it also includes our surplus in trade in services. If you just look at goods, the deficit is closer to 4.2% of GDP.

But even that doesn’t really explain very much, because it’s slightly lower than the 4.35% of GDP trade deficit in goods back in 2000. So again, the big loss of manufacturing jobs is something of a mystery. Yes, we import more goods than we used to, but exports of goods have risen at about the same rate since 2000. So why does it seem like trade has devastated our manufacturing sector?

Perhaps because trade interacts with automation. Not only do we lose jobs in manufacturing to automation, but trade leads us to re-orient our production toward goods that use relatively less labor (tech, aircraft, chemicals, farm produces, etc.), while we import goods like clothing, furniture and autos.

So trade and automation are both parts of a bigger trend, Schumpeterian creative destruction, which is transforming big areas of our economy. It’s especially painful as during the earlier period of automation (say 1950-2000) the physical output of goods was still rising fast. So the blow of automation was partly cushioned by a rise in output. (Although not in the coal and steel industries!) Since 2000, however, we’ve seen slower growth in physical output for a number of reasons, including slower workforce growth, a shift to a service economy, and a home building recession (which normally absorbs manufactured goods like home appliances, carpet, etc.) We are producing more goods than ever, but with dramatically fewer workers.