I went to a public school in Madison, Wisconsin during the 1960s. That’s one of America’s most egalitarian cities in one of the most egalitarian decades. Only in retrospect do I realize what a “weird” place it was. If you had told me in 1969 that a white person’s prospects in life depended on how rich their parents were I would have had no idea what you were talking about. To me, life seemed very simple. We almost all went to the Madison Public Schools, and the few who didn’t mostly went to Catholic schools of roughly equal quality. It seemed like success depended on some combination of being innately smart (or charismatic) and having a strong work ethic. I did not even know anything about the socio-economic class of my fellow students—what difference would it make if their parents were janitors or doctors? If college bound, we all tended to go to the UW, where tuition was $300/semester. And those that could not afford that pittance could get student loans. And college didn’t affect one’s income very much–a union job was just as good. I had two friends; the one from a low-income area was a better student than the one from a high-income area. Other than those two, I knew nothing about the family background of students, which seemed completely irrelevant to life’s success. (My uncle grew up in what we then called a “hillbilly family” in Kentucky, and was a distinguished professor at the University of Wisconsin.)

I’m not saying all this to try to convince you of anything. Madison in the 1960s was a very unusual place, and I undoubtedly missed a lot that was important even back then. But I tend to think of this background when reading the recent discussion of Raj Chetty’s work on income mobility. Tyler Cowen links to Megan McArdle, discussing Chetty’s work on upward mobility:

There’s no getting around it: For a girl raised on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, Salt Lake City is a very weird place.

I went to Utah precisely because it’s weird. More specifically, because economic data suggest that modest Salt Lake City, population 192,672, does something that the rest of us seem to be struggling with: It helps people move upward from poverty. I went to Utah in search of the American Dream.

I’m pretty sure McArdle’s experience in high school was quite different from mine (it can’t have been any worse.) Partly because New York was more diverse than Madison, and partly because (I assume) she’s more observant than I am, and far more than I was at age 14. But Utah doesn’t seem weird to me.

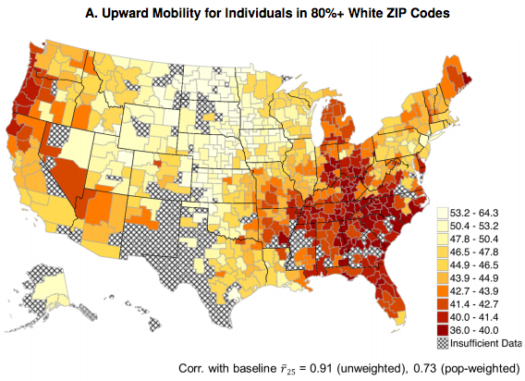

Madison is not Mormon, and it does have a lot of heavy drinking, but otherwise both places are part of Nordic America, the North Central part of the US. This map in Chetty’s paper shows higher levels of upward mobility (among whites) in lighter colors:

Actually, Madison’s on the fringe of Nordic America, the epicenter seems closer to South Dakota. (I had one Scandinavian grandparent.)

Actually, Madison’s on the fringe of Nordic America, the epicenter seems closer to South Dakota. (I had one Scandinavian grandparent.)

At one point McArdle compares the upward mobility of Utah and Denmark:

The wide gulf between Utah and, say, North Carolina implies that we do, in fact, have a real problem on our hands. A child born in the bottom quintile of incomes in Charlotte has only a 4 percent chance of making it into the top quintile. A child in Salt Lake City, on the other hand, has more than a 10.8 percent chance — achingly close to the 11.7 percent found in Denmark and well on the way to the 20 percent chance you would expect in a perfectly just world.

Interestingly she doesn’t pursue that link any further. Lars Christensen tipped me off to this fact:

Denmark supplied more immigrants to Utah in the nineteenth century than any other country except Great Britain. Most of these Danes–nearly 17,000–were converts to the LDS Church, heeding an urgent millennialistic call to gather to “Zion.”

Given that Denmark has less than 1% of Europe’s population, that’s a pretty interesting coincidence. And other Scandinavian countries were also well represented:

Periodicals in their native language served combined audiences of Danes and Norwegians, and sometimes Swedes as well. The most successful of these was the Danish-Norwegian newspaper Bikuben (The Beehive), published in Salt Lake City from 1876 through 1935 (under LDS Church ownership in later years).

Whatever’s going on in North Central America, and Utah as well, I’m pretty sure it has something to do with Nordic culture.

The title of this post includes “East Asians”; what do they have to do with Utah? The same Chetty paper has a table of mobility by metro area:

Notice that 3 of the top 6 cities are places in California with lots of upwardly mobile Asian families.

Notice that 3 of the top 6 cities are places in California with lots of upwardly mobile Asian families.

So let me finally get to the point. I see a similarity between North Central America (including Utah) and East Asia. In the not too distant past, both places were largely agricultural. But in the 21st century global economy the big money is no longer in farmland, it’s in ideas. Both areas have lots of upwardly mobile people who have successfully made the jump into the 21st century economy. Like me! (And my wife.) Lots of other cultures, in America and elsewhere, seem to struggle with the demand of the 21st century.

In one sense, the success of East Asia is easier to explain, because they started from a far lower level. When East Asia finally linked up with the global economy, they discovered that their cultures had a set of attributes that were well suited to achieving upward mobility—such as an emphasis on education, hard work, high saving rates, low crime rate, stable families, etc. Many of these cultural attributes also show up in North Central America. China is full of billionaires who started life as dirt-poor peasant farmers. I’d guess that 90% of the world’s billionaires who grew up in abject poverty are Chinese, and roughly zero percent are American.

But why do white Americans from Iowa and Utah have more upward mobility than white Americans from other areas. One possibility is that it’s easier to jump from the bottom 20% to the top 20% in places where those quintiles are not that far apart.

Lots of smart kids in the upward Midwest grew up in dead end small towns without much opportunity, but then used university education to make a jump to places where they could achieve much more success.

People on the two coasts tend to have a mental image of rural America as being “poor”. But the upper Midwest contains lots of pretty big and successful family farms. In the old days when America was more equal, talented people would have been much more content to stay in their region of the country. If they moved, it more likely was in search of a better climate. Why move from cold Wisconsin to cold Massachusetts when (during the 1960s) the incomes weren’t much different? High tech barely existed back then.

PS. What areas surprise you the most? For me, it’s the low upward mobility of Michigan and western Oregon, and the fact that Louisiana has more mobility than the rest of the Deep South.