Let’s start with an easier question. In what sense does OPEC control oil prices?

Imagine that OPEC produces 40% of the world’s oil. The cartel also has substantial excess capacity. Now let’s think about its control of global oil prices.

Because both the demand for oil and the supply of non-OPEC oil are relatively inelastic in the short run, OPEC has the ability to double global oil prices, or cut them in half, almost overnight. That’s a lot of control. So let’s assume that OPEC targets global oil prices at $100/barrel, and adjusts output to make the price stick.

There is one problem with this policy; oil supply and demand become far more elastic in the long run. So now let’s assume that the $100 oil price causes a fracking revolution, and non-OPEC supply rises sharply. To keep the price at $100/barrel, OPEC must reduce output to 35% of global production, then to 30%, then to 25%, etc., etc. They can do this for a while, but it’s painful.

OPEC also worries about the long run viability of the oil market, so eventually it decides that it’s no longer wise to keep the price at $100, even though in a technical sense it could continue doing so up until the point where its output fell to zero. OPEC decides that it is in their long run interest to face reality, and allow the fracking boom to reduce oil prices. There are two ways of making this happen

1. OPEC could stop controlling oil prices. They could instruct their members to produce a total of 40 million barrels per day, and let the market set the price.

2. They could keep controlling the price, but gradually reduce the price as needed to keep output at close to 40 million barrels per day (as fracking output rises). Thus they might reduce the price to $95 for a couple months, and then later to $90, and after another 3 months down to $85, etc. Prices would fall in a sort of step function, eventually hitting $45 after a few years. At each step of the way, price would be set at a level expected to keep OPEC output pretty stable, but once at that new price, output would be tweaked each day as needed to keep the price stable. Then after a few more months, another $5 price cut.

So in case #1 OPEC is not controlling global oil prices and in case #2 OPEC is controlling oil prices. But the two cases are actually pretty similar, and as you make the price adjustments smaller, the two cases get even more similar. Thus you could imagine the price being adjusted by $1 at a time, not $5, and the adjustments occurring much more frequently.

At what point do you move from a scenario where OPEC is controlling the global oil price to one where the market is controlling the global oil price?

Now let’s go back and think about the fracking boom, described earlier. Suppose OPEC actually responded to the fracking boom with the step function approach to lowering prices, described in case #2. So for periods of several months at a time, the price would be fixed by OPEC, then a sudden drop of $5/barrel. How would you think about this multi-year price decline, from $100 to $45? Does it make more sense to talk about the fracking boom causing a huge plunge in oil prices? Or should we say that OPEC caused a huge plunge in oil prices?

1. On the one hand, you could argue that OPEC controlled oil prices all through this period, and hence they caused the decline. They made the periodic adjustments in the official price, and all the time they had the ability to set world prices in a different position.

2. On the other hand, the fracking boom was the big disruptive force in the global marketplace. As fracked oil output soared, it caused global prices to fall. OPEC could have offset that, at least for a while, but they chose not to, keeping OPEC output close to 40 million barrels per day. OPEC did not take concrete steps to prop up oil prices.

Because terms like ‘cause’ are not well defined, there is no right answer. But in this case I think I’d prefer to say that the fracking boom caused the oil price plunge. And I don’t think it’s just me; many economic pundits would view that as a plausible way of describing what caused the big plunge in oil prices.

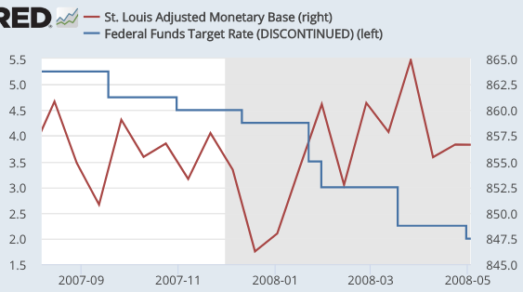

It turns out that this example is uncannily similar to the plunge in interest rates from July 2007 to May 2008. Before going over that example, recall an important aspect of the previous example. I said that while in the short run OPEC could have continued holding oil prices up at $100 for an even longer period, they also had long term objectives to think about, which made them conclude that it was wise to allow some price decline, so that their long term hold on the oil market would not be completely lost.

Now think about the Fed during 2007-08. Real estate is declining sharply, and there are many fewer mortgages being issued. The lower demand for credit puts downward pressure on interest rates. For the Fed to prevent interest rates from falling, they’d have to continually reduce the monetary base. That sort of tight money would keep rates from falling below 5.25% (via the liquidity effect).

But the Fed realizes that if it did what it took to prevent rates from falling, then this policy would disrupt its long run goals for the economy. Big time! So instead of reducing the monetary base it decides to allow interest rates to fall, while holding the base fairly stable. There are two ways it could do that:

1. It could hold the base roughly stable at $855 billion (plus or minus 1%), and completely stop targeting interest rates. Let the market set interest rates.

2. It could instruct the New York Fed to reduce rates by ¼% or ½% every few months, as needed to keep the base fairly stable. On days when the official fed funds target was not being adjusted, the New York Fed would hold rates stable with small adjustments in the base, up and down.

You could also envision intermediate cases, like the official fed funds rate target being adjusted in 5 basis point steps, instead of 25 basis point steps. The smaller the adjustments, the more it would look like the market was setting the rate at a level that resulted in a stable monetary base.

I would argue that case #1 and case #2 are actually pretty similar. But in case one it looks like the market is setting interest rates, and in case two it looks like the Fed is controlling interest rates.

Now let’s return to the weak credit markets, caused by the housing depression. Does it make more sense to talk about weak credit markets depressing interest rates? Or should we say the Fed caused interest rates to fall during 2007-08? And if the latter, exactly how did the Fed cause interest rates to fall? After all, they did not increase the monetary base, which is their usual way of causing interest rates to fall. (This is pre-IOR).

Opinions will differ, but I think it’s more useful to talk about weak credit markets causing a decline in interest rates, and the Fed just sort of getting out in front of the parade by adjusting its official target as the “natural rate of interest” fell during 2007-08. But since the Fed always has the technical ability to move the actual interest rate away from the natural rate, at least for a period of time, others will prefer to say that the Fed caused interest rates to decline. I would not strongly object to that claim. Still, it is interesting that while other pundits would agree with me on the fracking boom example, they’d probably disagree here, insisting it was the Fed that cut rates.

What I would strongly object to is the claim that the Fed caused interest rates to fall during 2007-08 with an easy money policy. I defy anyone to come up with a coherent definition of easy money, which would imply that money was easy during 2007-08 (when nominal rates fell), and also easy during the second half of 2008 (when real rates soared), and was also tight during the Argentine hyperinflation of the 1980s (when the base soared).

I recently gave a talk at Kenyon College, and this post (along with another at Econlog) was motivated by a discussion with Will Luther. He directed me to an earlier post of his:

I was pleased to see David Henderson call out Bill Poole for claiming the Fed sets the federal funds rate. It doesn’t, of course. Welcome to the Wicksell Club, David! We don’t have ties or t-shirts. But our common cause is worthwhile.

Many of my economist friends get annoyed when I insist they refer to setting the federal funds rate target (as opposed to setting the federal funds rate). They know that the Fed is not literally setting the federal funds rate; that the rate is determined by suppliers and demanders in the overnight market; and that the Fed, as Bernanke has made clear, has a limited influence on even short term rates. But, they maintain, it is a convenient shorthand of little consequence.

I disagree. Perhaps I have spent too much time in a liberal arts environment, but I believe the language we use matters. In this case, the dominant Fed-sets-rate language makes it easy to assume that the federal funds rate is low because the Fed’s target is low. It makes it difficult to even consider the possibility that the Fed’s target is low because the market-clearing federal funds rate is low. Moreover, it suggests the Fed is in a direct and dominant position when, in fact, the Fed plays an indirect role and, at least by my assessment, is subservient to routine market forces. It also seems to perpetuate the all-too-common error of associating low rates with expansionary monetary policy and high rates with contractionary monetary policy. (Scott Sumner is right: Interest rates are not a reliable indicator of monetary policy.)

The Mercatus Center is a good resource for papers that discuss this issue. Check out Jeffrey Hummel’s paper. A somewhat related paper by Thomas Raffinot is also useful.