Consider a country with a very simple monetary base, just government issued coins made out of gold, silver and copper. And then someone decides that it would be more efficient to supplement the coins with paper money in larger denominations. Initially, only commercial banks are allowed to hold currency. They use the currency to clear balances between banks.

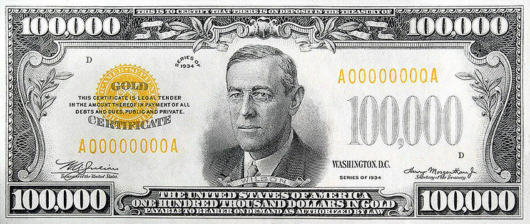

This example is not historically accurate, but it’s also not as far-fetched as it seems. Back in 1912, the entire monetary base was cash and coins, and very large bills were used almost exclusively to clear balances between banks:

Obviously it would be a weird system, and in fact the public always has been allowed to hold currency notes and coins.

Now imagine that the public can hold currency and a third type of base money is created, non-interest bearing deposits at the central bank, which are a sort of “electronic cash” that doesn’t face the risk of theft or fire. Once again, let’s assume that only commercial banks were allowed to hold this new and more efficient type of government created base money. That would be kind of weird, wouldn’t it? It certainly seems weird to me. But that’s exactly what we did in 1913.

Tyler Cowen has a new post that discusses proposals for central banks to create e-currency:

The various proposals are works in progress, but share one basic feature: Central banks would issue electronic deposits. These deposits would be available to eligible citizens or businesses, allowing a greater number of parties direct access to the accounting and payments mechanisms of the central bank. One simple version of the proposal would let individuals hold an account at the Federal Reserve, just as they can hold an account at Bank of America. It would be like a “public option” for banking, albeit with an electronic focus and direct access to the Fed.

I think it’s misleading to suggest these accounts are sort of like a bank account at Bank of America. If I have $10,000 in bills in a shoebox under my bed, is that sort of like an account at BOA? Clearly not. A commercial bank account is a loan of money from me to a commercial bank. A box of cash under my bed is not really a loan of money to the government in the conventional sense of the term (although it may be a sort of zero interest quasi-loan if the government commits to stabilize its value.) But a loan to BOA is risky, whereas a loan to a fiat money central bank is no more risky that holding cash. It may lose value from inflation, but default is very unlikely.

BTW, there is already a “public option” for deposits at the Fed, but it’s only for commercial banks.

On the other hand, deposits at the Fed would compete with commercial bank deposits, as commercial banks thrive on their ability to offer a close substitute for a deposit at the central bank—a commercial bank deposit insured by taxpayers at up to $250,000.

Tyler worries that this might put us on the path to a more socialist economy:

An alternative scenario is that the central bank decides to enter the commercial lending business, much as your current bank does. Will the central bank be a better lender than the private banks? Probably not. Central banks are conservative by nature, and have few “roots in the community” as the phrase is commonly understood. The end result would be more funds used to buy Treasury bonds and mortgage securities — highly institutionalized investments — and fewer loans to small and mid-sized local businesses.

This seems to mix up two issues. We’ve already essentially socialized the deposit side of the banking industry, at least from a risk perspective. Tyler suggests that this might lead central banks to begin lending to ordinary businesses. But if that were to happen it would mean we were already far down the road to socialism, and it’s not likely to hinge on a minor issue like whether or not the public is allowed to hold base money in deposits at the Fed.

I understand that many free market economists are skeptical of allowing central banks to offer deposits to the public. So am I. Indeed I’m probably about the only person in the world who has advocated totally abolishing accounts at the Fed, even for banks, and going back to the cash and coin monetary base of 1912. That system seemed to work fine (at least in Canada, where they didn’t have an insane set of banking regulations.) So I’m hardly a socialist on this issue. More like a reactionary.

On the other hand, I wish free market economists gave a bit more thought as to why both the public and banks can hold two of the types of base money (coins and currency) but only banks can hold the third (deposits at the central bank.) There may be a reason for that asymmetry, but I’ve never seen a convincing explanation.

Here’s Tyler:

This leads to my primary objection to an official government e-currency: It would, in effect, make many more economic institutions more like banks. Over time, those institutions would probably be regulated more like banks, too. For instance, if the Fed is directly transmitting payments made by a private company, it might be wary of credit risk and impose capital and reserve requirements on that company, much as it does on banks. Banks also might complain that they are facing unfair competition, and ask that consistent regulations be imposed. In any case, more of the economy likely will be subject to financial regulation, not just the relatively narrow core of the banking system.

I don’t follow this. Where is the risk in the public having deposits at the central bank? I don’t get regulated for having a shoebox of cash under my bed, why would moving that money into an account at the Fed cause the government to begin regulating me like a bank?

Again, I’m not saying that offering Fed accounts to the public is a good idea. Rather I’m waiting for free market economists to give me a plausible explanation as to why these deposits are not a good idea for the public, but are a good idea for commercial banks. What makes banks so special that they deserve this subsidy? Isn’t this like when the government says that only car dealers can sell new cars, not manufacturers? We don’t have a special regulatory burden on banks because they have deposits at the Fed, we have special regulations for banks because of FDIC and too-big-to-fail, which exposes taxpayers to losses resulting from moral hazard.

PS. One compromise might be to allow both the public and banks to have deposits at the Fed, but insist that they not earn any interest. That would make clearer their essential “cash-like” nature.

PPS. Whatever we do, I’m certain that it will be the wrong thing. Banks have way too much political power and any new regime will undoubtedly cater to their interests.