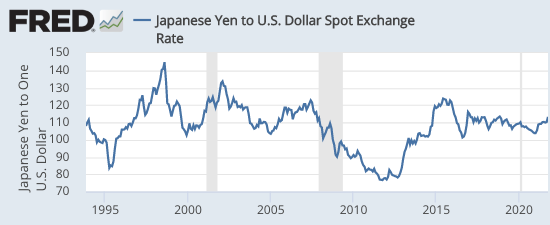

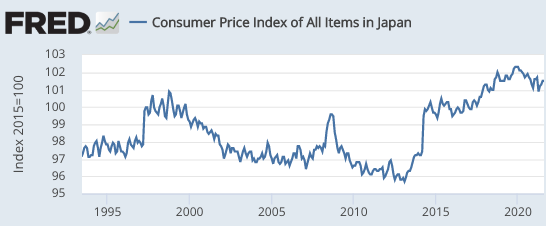

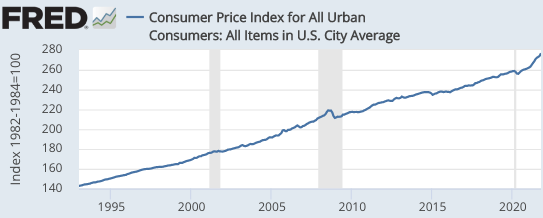

Over the past 28 years, the dollar/yen exchange rate has behaved very oddly. During this period, Japan’s CPI has risen by 4%. Not 4%/year, rather 4% in total. And even that merely reflects a set of sales tax increases. Meanwhile, the dollar has appreciated by about 6% against the yen (in nominal terms). If we combined those two facts, and apply the theory of purchasing power parity (PPP), then you might have expected the US price level to have fallen by about 2%. Instead, it rose by 90%.

This means that the US real exchange rate appreciated by roughly 92% against the yen. That’s a lot!

Each year, I expect PPP to finally kick in. But over the past 12 months, the US CPI rose by 6.2%, while the Japanese CPI fell slightly. So did the dollar depreciate? No, it’s up almost 8% against the yen, for a real appreciation of nearly 14%. (Japan is becoming a real travel bargain.)

So why don’t I give up on my belief in PPP? Why do I still believe that the optimal forecast of the real exchange rate for the dollar against the yen in the year 2049 (28 years from today) is roughly the same as the real exchange rate today? The answer is simple. The logic behind PPP is so powerful that almost any anomaly is easier to explain as being due to a one-time adjustment in Japan’s real exchange rate, rather than PPP being wrong. Ceteris paribus, I still expect US/Japan inflation differentials to show up in future movements in the nominal exchange rate.

Here’s another example. Over the past 28 years, the NASDAQ stock index has massively outperformed British and French stock indices. And yet, if asked to predict which index will do the best over the next 28 years, I’d predict they do about the same. And the reason is simple. The logic behind the Efficient Markets Hypothesis is incredibly powerful. Rather than reject the EMH, it’s easier to explain this huge NASDAQ outperformance as a one-time unanticipated adjustment in response to US tech firms doing better than they were expected to do back in 1993.

People often respond to these explanations with, “Oh come on, for 28 years?”

Apparently so.