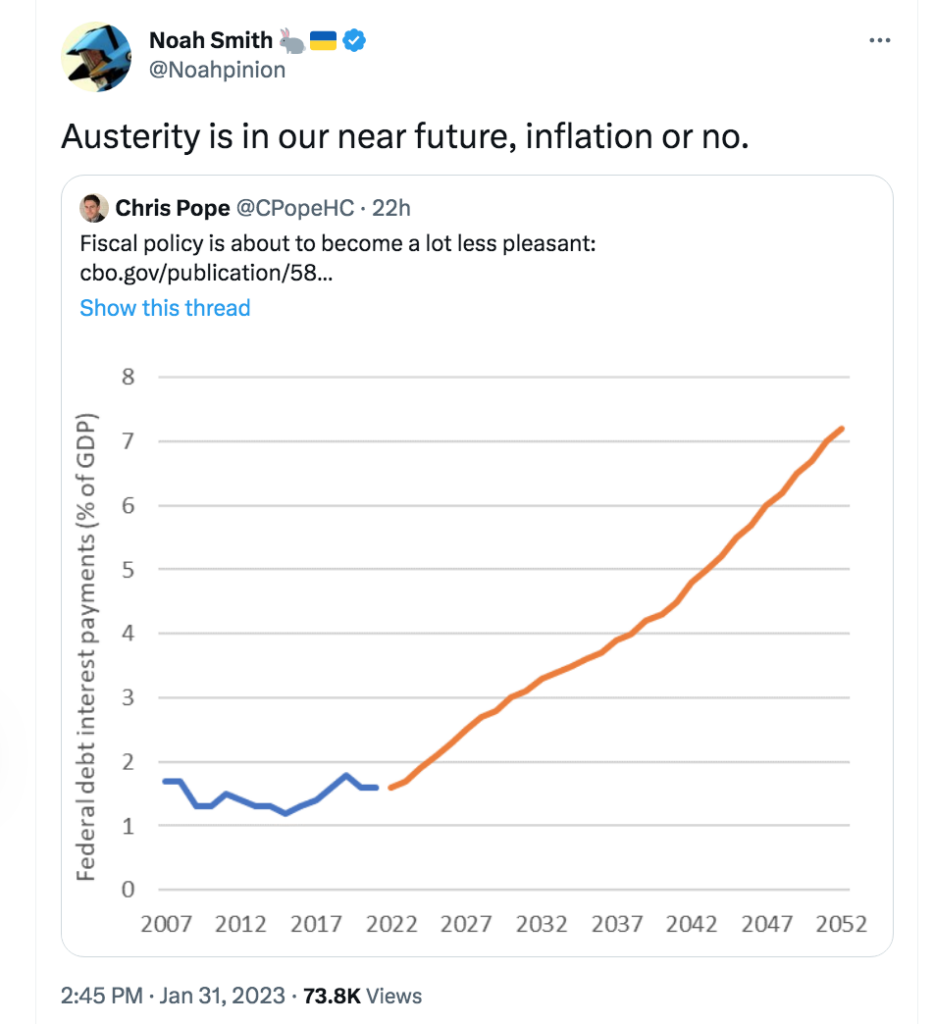

For years I’ve been warning that reckless fiscal policy (under Trump and Biden) would lead to future tax increases. And for years I’ve been attacked as an old fogey who doesn’t understand that we are in a new era of zero interest rates, a new era of free credit forever.

Here’s Noah Smith:

Monetary policy is about aggregate demand. Fiscal policy is about efficiency. The profession made a huge mistake in conflating the two policies.

PS. There are a few signs the economy might actually be speeding up:

Vacancies at US employers unexpectedly increased at the end of 2022, illustrating a solid appetite for labor that the Federal Reserve sees as one of the last hurdles to bring down inflation.

The number of available positions climbed to a five-month high of just over 11 million in December from 10.4 million a month earlier, the Labor Department’s Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, or JOLTS, showed Wednesday. The increase was the largest since July 2021 and mostly reflected a jump in vacancies in accommodation and food services.

(While I’m doing my annoying “I told you so” routine, I might as well add that I ridiculed those who claimed two falling quarters of GDP meant we were in recession during early 2022. I don’t recall any previous recessions with record job openings.)

Tyler Cowen has a post discussing the possibility of the economy reheating, and has this to say:

Another possible pathway for these scenarios involves interest rates. During a normal disinflation, the Federal Reserve raises rates and keeps them high for a long period of time while the economy adjusts slowly — often passing through recession. But inflation has fallen more rapidly than expected, and so the market may expect the Fed to lower interest rates sooner than planned. And an expected cut in interest rates can encourage expansionary pressures just as much as an actual cut in interest rates.

It is a funny world in which slow inflation can cause faster inflation. It’s the logic of expectations that makes it possible, albeit far from certain.

Of course this would not be a case where low inflation is directly causing high inflation. Rather, if this happened it would be a case of the Fed looking at inflation when it should be looking at NGDP growth, and wrongly concluding that monetary restraint is no longer needed. Persistently excessive inflation is always and everywhere a monetary policy failure.