The old TV sitcom Cheers began with a nostalgic song about a time and place “where everyone knows your name”.

Welcome to Dubai:

Mr Williams contrasts “the dreaded 90-minute queue at a US airport to deal with an immigration officer who rarely seems pleased you’ve come to visit” with the UAE’s high-tech system. Arriving in Dubai, “My passport stays in my pocket, the camera recognises me, the screen says, ‘Hello Simon J. Williams’ and the gate opens.” He feels both more welcome and more secure.

Heartwarming? 1984? Or both?

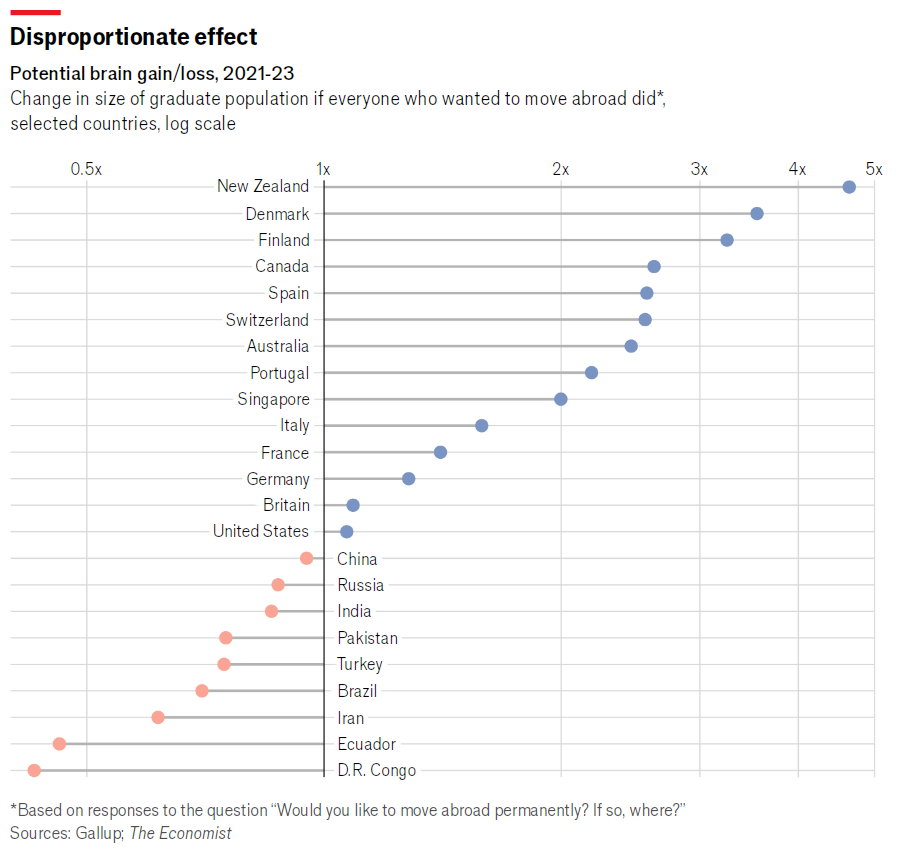

The preceding quote is from an excellent article in The Economist, which looks at where people would move if the world had completely open borders for college grads. The three winners are:

1. In gross terms, the USA.

2. In net terms, Canada.

3. In percentage of population terms, New Zealand.

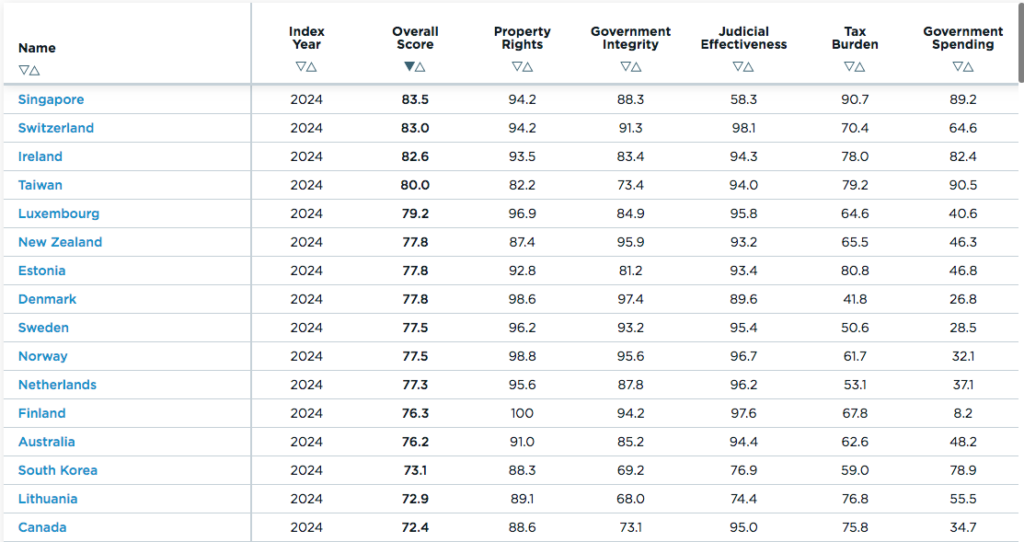

If you look at the nine countries where the graduate population would at least double, seven are near the top of the Heritage Foundation’s Economic Freedom rankings (in the top 16 out of 184 countries), and the other two have a pleasant lifestyle and a good location (Spain and Portugal.)

Here is the top of the Heritage economic freedom ranking:

No USA?

In gross terms, the US remains the most desired destination, but Canada leads the world in net terms (black dots), by an impressive margin (with Australia #2):

The morons in Washington DC don’t understand this yet, but in the 21st century the battle for global supremacy will depend far more on a country’s ability to attract global talent than on its “industrial policies”:

The smartest people are highly mobile. Only 3.6% of the world’s population are migrants. But of the 1,000 people with the highest scores in the entrance exam for India’s elite institutes of technology, 36% migrate after graduation. Among the top 100, 62% do. Among the top 20% of ai researchers in the world, 42% work abroad, according to MacroPolo, a think-tank in Chicago.

The US remains a very attractive destination, but also puts up much more formidable barriers than many other destinations:

Yet when he wanted permanent residence, he faced a snag. America mandates that no country may receive more than 7% of green cards in a given year. This is tricky for applicants from populous countries, such as the Indian-born Mr Das. A typical Indian applicant can expect to wait 134 years for approval, estimates the Cato Institute, a think-tank.

The US and China are both their own worst enemy. The winner will be country that puts the fewest bullets into its own foot.