This is part 4 from the paper “Understanding the Modern Monetary System. To read the first sections please see Part 1 here, part 2a here, Part 2b here & part 3 here.

Part IV – The Lead Role of the Private Sector & “Inside Money”

Understanding the Economic “Machine”

The economic system is similar to a machine. The metaphor of a car is useful to understand how all the pieces fit together. Monetary policy is akin to the brake and accelerator pads. When the central bank raises the Federal Funds Rate it does so typically to suppress inflationary pressures by making it less enticing for banks to issue loans (create money). When the Fed increases the Federal Funds Rate (i.e. the short-term interest rate on which monetary policy pivots) this raises borrowing costs across the spectrum of credit products thus putting a brake on economic activity. Vice versa when the Fed lowers the Federal Funds Rate, typically to counteract a swelling in the number of underemployed, this decreases borrowing costs across the spectrum of credit products (especially loans made on a shorter-term basis) thus accelerating economic activity. Monetary policy is mainly about manipulating short-term interest rates though there are other factors.

Fiscal policy is the gear stick. Economists often talk about aggregate supply and aggregate demand. The former is the total amount of final goods and services produced by an economy over a given time period. The latter is the total amount of final goods and services purchased by agents over a given time period. What we produce as a nation and the market prices at which goods and services are sold can be different; hence, the labels of aggregate supply and aggregate demand. When the economy is booming during an upswing aggregate demand can exceed aggregate supply leading to inflationary pressures. When the economy is depressed during a downturn aggregate supply can exceed aggregate demand leading to disinflationary or even deflationary pressures. If the economy is suffering from a lack of aggregate demand the government sector can, through larger deficits (i.e. spending in excess of revenues), shift the economy up a gear (please note this can be achieved through lower taxes OR higher spending). In fact, as tax receipts and certain government outlays (e.g. unemployment benefits) both rise and fall in a countercyclical fashion, much of the federal government’s budget stance is beyond the control of policymakers and instead determined by the endogenous performance of the economy. This is known as automatic stabilizers. Things like unemployment benefits and other “automatic” forms of spending can rise without any new government action during a downturn.

Increases in government spending increase the flow of funds in the economy and help to improve private balance sheets. This occurs through two primary functions. The first being the fact that the government can always procure funds and increase the flow of spending in the economy. That is, when the private sector stops spending and investing (for whatever reason) the government can always turn on the “flow” and increase incomes, revenues, etc. The second impact occurs in the form of increases in net financial assets which can help improve the stability of private balance sheets. Remember, when the government deficit spends it sells a bond to Peter and redistributes Peter’s bank deposits to Paul. The bond sale to Peter results in a net financial asset for the private sector because there is no private sector liability attached to it. Of course, if government spending is poorly allocated or malinvested there can be negative long-term consequences through various channels. This should not be overlooked or underemphasized.

As Michael Kalecki has famously noted, Government deficits (whether it be via lower taxes or increased spending) can also help sustain the revenues and profits of businesses enabling them to employ more people.12 You may have noticed the sharp rebound in corporate profits over the course of the post-financial crisis period. This was due, in large part, to government deficit spending; though as of 2012 it has failed to translate into a strong and sustainable recovery. I won’t dive into this in great detail, but the reason for this is rather simple as seen in the following equation derived from Kalecki’s work:

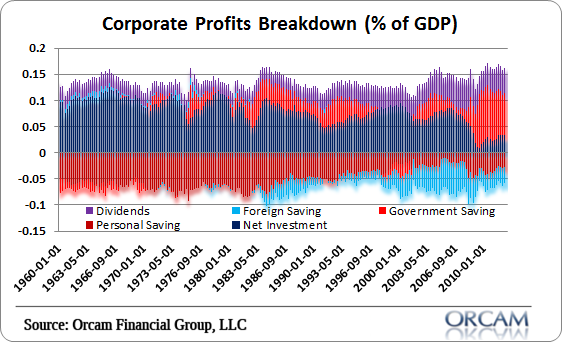

Profits = Investment – Household Savings – Government Savings – Foreign Savings + Dividends

This equation can be seen in visual form below. This shows the breakdown of corporate profits as a percentage of GDP since 1960. As you can see, the primary driver of corporate profits is almost always net investment. So the private sector is the primary driver of profit growth most of the time. The crisis of 2008 was unusual in that the de-leveraging led to a sharp decline in net investment. The bright red bars, or the government’s spending, led to a substantially larger role in driving corporate profits during this period as a result of this private investment collapse.

(Figure 4 – Corporate Profits as % of GDP)

Continuing on with the metaphor, government regulation can be a nuisance (bureaucratic red tape) but when not overdone it is like the safety features built into modern cars (e.g. seatbelts, airbags, etc.) with the purpose to keep economic activities within acceptable boundaries, but without constraining the vehicle from moving. In some respects the government sector is like a “safety net” there to correct and curb market failures (though admittedly, it can also exacerbate problems if misunderstood). In a similar fashion to the role of outside money as a facilitating feature of the money system, government regulation can facilitate stable growth when not overdone.

Hyman Minsky has noted that capitalist economies are periodically prone to what he called “endogenous” financial instability by which he meant that the “normal” workings of the market system can generate financial excess. He advised on the need to update regulation in view of new developments and for policymakers and theorists alike to humbly acknowledge the possibility that what worked in the past may no longer do so. Minsky was overlooked. I believe that humans are inherently fallible and inherently irrational. Since economies are the summation of the decisions of these irrational actors it is not surprising that the economy has a tendency to veer in the direction of extremes at times. As Minksy famously noted, “stability breeds instability” as economic agents become increasingly comfortable and complacent during the boom phase of the business cycle which can lead to excess and bust.

Everything else in the car is the private sector. The nonfinancial business sector is the engine, the chassis, the wheels and the seats (what we might think of as the “core” pieces of the car). Nonfinancial businesses are the biggest employers and make most of the products and services essential to increasing living standards. The household sector is the driver and any passengers in the car. As employers, employees, investors and consumers we determine the overall direction of the economic system. The financial sector provides the lubricants in the car (e.g. the oil, coolant, etc). The main role of finance is to facilitate the development of the productive capital assets of the economy and to provide the monetary and financial resources that allow us to undertake activities of our own liking (e.g. buy or build homes). The fuel in the car that motors the economic system is the drive to earn a living, make a profit and save for the future.

The Myth of the Money Multiplier & Banking Basics

The US monetary system is designed to cater for the creation of the public’s money supply primarily by private banks. Most modern money takes the form of bank deposits and most market exchanges involving private agents are transacted in private bank money: it is “inside money“ which rules the roost so to speak in the day-to-day functioning of modern fiat monetary systems. The role of the public sector “outside money” creation is comparatively minor and plays a mostly facilitating role.

Like the government, banks are also money issuers, but not issuers of net financial assets. That is, banking transactions always involve the creation of an asset and a liability. Banks create loans independent of government constraint (aside from the regulatory framework). As we will explain below, banks make loans independent of their reserve position with the government rendering the traditional money multiplier deeply flawed.

The monetary system in the USA is designed specifically around a competitive private banking system. The banking system is not a public/private partnership serving public purpose as the Federal Reserve essentially is. The banking system in the USA is a privately owned component of the system run for private profit. This was designed in order to disperse the power of money creation away from a centralized government and into the hands of non-government entities. Because the Fed finds itself as an agent of the US government working its policies primarily through these private entities it is often the center of much controversy. This will at times appear like a conflict of interest as the Federal Reserve, an agent of the government, is often seen as being in collusion with the banks and at odds with the achievement of public purpose. The government’s relationship with the private banking system is more a support mechanism than anything else. In this regard, I like to think of the government as being a facilitator in helping sustain a viable credit based money system although the banks as private profit seeking entities sometimes find their motives at odds with the overall goal of public purpose.

It’s important to understand that banks are unconstrained by the government (outside of the regulatory framework) in terms of how they create money. When we go through business school we are taught that banks obtain deposits and then leverage those deposits up by 10X or so. This is why we call the modern banking system a “Fractional Reserve Banking” system. Banks supposedly lend a portion of their “reserves”. There’s just one problem here. Banks are never reserve constrained! Banks are always capital constrained. This can best be seen in countries such as Canada where there are no reserve requirements.13 Reserves are used for only two purposes – to settle payments in the interbank market and to meet the Fed’s reserve requirements. Aside from this, reserves have very little impact on the day-to-day lending operations of banks in the USA. This was recently confirmed in a Fed paper:

“Changes in reserves are unrelated to changes in lending, and open market operations do not have a direct impact on lending. We conclude that the textbook treatment of money in the transmission mechanism can be rejected.”14

This is very important to understand because many have assumed that various Fed policies in recent years (such as Quantitative Easing) would be inflationary or even hyperinflationary. But all the Fed has been doing is adding reserves to the banking system in exchange for (mostly) government bonds. Because banks are not reserve constrained, i.e, they don’t lend their reserves or multiply their reserves, this doesn’t necessarily lead to more lending and will not result in the private sector being able to access more capital.

Because banks are not reserve constrained it can only mean one thing – banks lend when creditworthy customers have demand for loans (assuming the banking system is healthy and banks are engaging in the business they are designed to transact). Loans create deposits, not vice versa. Banks create new loans independent of their reserve position and the Federal Reserve is in the business of altering the composition of outstanding financial assets in an effort to maintain a target interest rate and maintaining the smoothly operating payments system that it oversees (this is part of monetary policy which only loosely impacts the direct issuance of inside money). In the loan creation process, banks will make loans first (resulting in new deposits) and will find necessary reserves after the fact (either in the overnight market or via the Fed).

Understanding the business of banking is rather simple. It’s best to think of banks as running a payments system that helps us all to transact within the economy. In addition to helping manage this payments system they issue money in the form of loans. Banks earn a profit in the means of transacting business when their assets are less expensive than their liabilities. In other words, banks need to source their ability to run this payments system smoothly, but will seek to do so in a manner that doesn’t reduce their profitability.

Banks don’t use their deposits or reserves to create loans, however. Banks make loans and find reserves after the fact if needed. But since banking is a spread business (having assets that are less expensive than liabilities) the banks will always seek the cheapest source of funds for managing their payment system. That just so happens to generally be bank deposits. This gives the appearance that banks “fund” their loan book by obtaining deposits, but this is not necessarily the case. It is better to think of banking as a spread business where the bank simply acquires the cheapest liabilities to sustain its payment system and maximize profits.

To illustrate this point let’s briefly review the change in balance sheet composition between banks and households before and after a loan is made. Since banks are not constrained by their reserves the banks do not need to have X amount of reserves on hand to create new loans. But banks must have ample capital in order to be able to operate and meet regulatory requirements. Reserves make up one component of the bank balance sheet so it’s better to think of banks as being capital constrained and not reserve constrained.

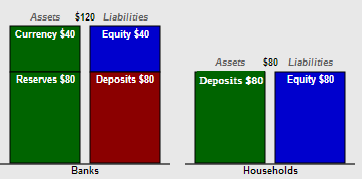

Let’s start with a simple money system as displayed below. In this example banks begin with $120 in assets and liabilities comprised of currency, reserves, equity and deposits. Of this, households hold $80 in deposits which are assets for the households and liabilities for the banking system. That is, the bank owes you your deposit on demand.

(Figure 5 – Before Loan is Made)

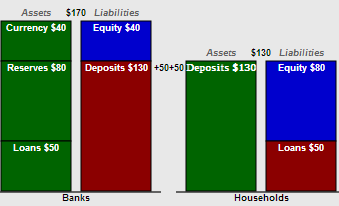

Our banking system has reserves already, but this is not necessary for the bank to issue a loan. It must simply remain solvent within its regulatory requirements. But if our households want to take out a new loan to purchase a new home for $50 the bank simply credits the household’s account as seen in Figure 6. When the new loan is made household deposits increase to $130. Household loans increase by $50. Bank assets increase by $50 (the loan) and bank liabilities increase by $50 (the deposit).

If the bank needs reserves to help settle payments or meet reserve requirements it can always borrow from another bank in the interbank market or if it must, it can borrow from the Federal Reserve Discount Window.

(Figure 6 – After Loan is Made)

The post Understanding the Modern Monetary System – Part 4 appeared first on PRAGMATIC CAPITALISM.