Some observers believe the Fed’s large scale asset purchases (LSAPs) are actually a drag on the economy. They note that the Fed’s purchases of treasuries is reducing the supply of safe assets, the assets that effectively function as money for the shadow banking system. They do this by serving as the collateral that facilitates exchange among institutional investors. Critics, therefore, contend that LSAPs are more likely to be deflationary than inflationary. A recent piece by Andy Kessler in the WSJ typifies this view:

So what’s the problem? Well, it turns out, there’s a huge collateral shortage. Global bank-reserve requirements have changed, meaning more safe, highly liquid securities like Treasurys are demanded instead of, say, Greek or Cypriot debt. And lately, Treasurys have been getting harder to find. Why? Because of the very quantitative easing that was supposedly stimulating the economy. The $1.8 trillion of Treasury bonds sitting out of reach on the books of the Fed is starving the repo market of safe collateral. With rehypothecation multipliers, this means that the economy may be shy some $5 trillion in credit…

[T]the Federal Reserve’s policy—to stimulate lending and the economy by buying Treasurys, and to keep stimulating until inflation reaches 2% or unemployment is lower than 6.5%—is creating a shortage of safe collateral, the very thing needed to create credit in the shadow banking system for the private economy. The quantitative easing policy appears self-defeating, perversely keeping economic growth slower and jobs scarce.

So is the Fed really “squeezing” the shadow banking system as Kessler claims? Are the LSAPs actually stalling the recovery rather than supporting it? In a word, no, as this view misses the forest for the trees at two levels. First, by focusing on the Fed’s LSAPs of safe assets, this understanding overlooks the more important contributors to the safe asset shortage. Second, this view takes a static view. It doesn’t consider the dynamic effect of LSAPs on the supply of private safe assets. Let’s consider each point in turn.

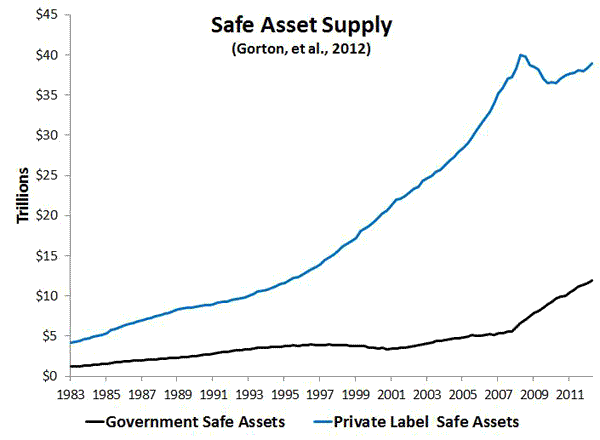

First, the main reasons for the safe asset shortage are (1) the destruction and slow recovery of private label safe assets since the crisis and (2) the elevated demand for safe assets that has arisen during this time. The importance of the first develpment can be seen in the figure below. It shows the Gorton et. al. (2012) measure of safe assets broken into government and privately-created safe assets. The figure shows an almost $4 trillion dollar fall in private label safe assets during the crisis. The Fed’s purchases of treasuries has no direct bearing on this private supply shortage (though I will argue below it has a positive indirect effect on it).

This reduction in the supply of safe assets occurred, of course, just as the demand for safe assets were rising in 2008. Since then, a spate of bad news–Eurozone crisis, China slowdown concerns, debt limit talks, fiscal cliff talks–has kept the demand for safe asset elevated as well as new regulatory requirements requiring banks to hold more safe assets. It is these developments that are the real stranglehold on the shadow banking system.1

Still, Kessler and other critics are correct to note that the immediate effect of the Fed’s LSAPs, even if relatively minor, is to reduce collateral in the shadow banking system. However, this narrow focus misses the potential for the LSAPs to catalyze the private production of safe assets. The LSAPs, if done right, should raise expected economic growth going forward and cause asset prices to soar. This, in turn, would increase the current demand for and supply of financial intermediation. For example, AAA-rated corporations may issue more bonds to build up productive capacity in expectation of higher future sales growth. Financial firms, likewise, may start providing more loans as the improved economic outlook makes households and firms appear as better credit risks. Critics like Kessler miss this dynamic effect of LSAPs.

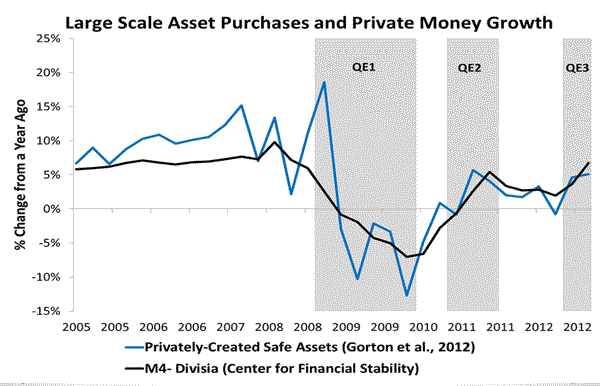

The potential for LSAPs to spur private safe asset creation is not just theoretical. It appears to be happening already with Abenomics in Japan. And to a lesser extent, it has been happening in the United States with QE2 and QE3. Now, these two LSAPs programs are far from perfect, but even they appear to have supported some private safe asset creation. This can be seen in the figure below which shows the year-on-year growth rate of the Gorton et. al. (2012) measure of private safe assets. It also reports the year-on-year growth rate for the “M4 minus” Divisia measure from the Center for Financial Stability. This metric provides an estimate of the broad money supply, including shadow banking money assets but excluding treasuries (the “minus” part). This measure, then, is also capturing the supply of private safe assets. The figure indicates that under both QE2 and QE3, the growth rate of private safe assets increased. Unlike QE1 which was designed to save the financial system, the latter two QE programs were explicitly geared toward shoring up the economy. In so doing, they also appear to have ramped up the production of private safe assets.

QE3 is still ongoing and continues to support more private safe asset creation. The recent rise in treasury yields is another sign of this process as it indicates a rebalancing of portfolios toward, among other things, private safe assets. Now there is a long ways to go before there will be enough private safe assets to restore full employment NGDP growth. But we are on the way–the only way since there is a limit to the amount of safe assets the government can provide without jeopardizing its risk-free status–and this should not be ignored by critics like Kessler.

The appropriate critique, then, of the Fed is not that it is squeezing the shadow banking system, but that it has failed to do enough to undo the stranglehold on it coming from the shortfall of private safe asset creation and the elevated demand for safe assets.

P.S. John Cochrane reads Andy Kessler’s piece too. He wonders if the monetary base is losing its special standing as high-powered money since treasuries have become high-powered money for the shadow banking system. The answer is no because the monetary base is still the medium of account, a huge advantage. Also, though the monetary base and treasuries may be near perfect substitutes today, they won’t be in the future. And investors make their decisions based largely on what they think will happen in the future. Thus, a monetary base injection today that is expected to be permanent and greater than the demand for the monetary base in the future is likely to affect spending today, even though treasuries and the monetary base are now close substitutes. The key is creating the belief that monetary base injection will be permanent, a point repeatedly made by Michael Woodford.