More than six decades after Taiwan’s estrangement from mainland China, the Taiwan Strait still represents the most physically formidable and symbolically inaccessible barrier to Beijing’s objective of eventual reunification with the island. Over the course of its history, Taiwan switched hands from European and Japanese colonial occupiers before becoming the prospective battleground between China and Taiwan in the second half of the 20th century. In recent years, military tensions between China and Taiwan have eased, and Beijing hopes that enhanced economic integration and the physical infrastructure it wants to build one day across the Taiwan Strait could bring the country a step closer to fulfilling a core geopolitical imperative by reuniting with the island.

Analysis

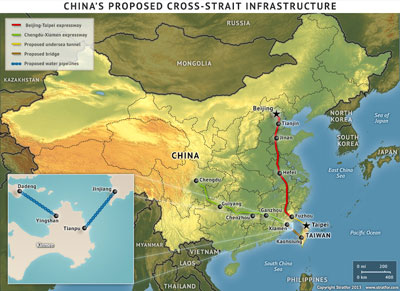

The South China Morning Post reported Aug. 5 that in its recently approved National Highway Network Plan for 2013-2030, the State Council included two highway projects linking Taiwan to the mainland. One involves the long-proposed Beijing-Taipei Expressway, which would start in Beijing and pass through Tianjin, Hebei, Shandong, Jiangsu, Anhui, Zhejiang and Fujian’s Fuzhou before crossing the strait and reaching Taipei. Another inland route would start in Chengdu and pass through Guizhou, Hunan, Jiangxi and Fujian’s Xiamen, and cross the Taipei-administered Kinmen archipelago before eventually ending at Kaohsiung in southern Taiwan.

The plan does not specify what kind of infrastructure — a bridge or a tunnel, for example — would be used to connect the mainland to Taiwan over the 180-kilometer (111-mile) strait, but since 1996, if not earlier, Beijing has publicly called for such infrastructure to be built. One proposal involved a 122-kilometer undersea tunnel, which was deemed preferable because of its relative seismic stability and its location in shallower water. This tunnel would connect Fujian province’s Pingtan Island to Hsinchu in northern Taiwan — a distance nearly three times that of Channel Tunnel, which connects the United Kingdom and France — and would cost an estimated 400 billion-500 billion yuan ($65 billion-$81 billion) to build. Another proposal involves linking Taiwan’s southern Chiayi county to the outlying island of Kinmen via tunnel or bridge, where it would connect with envisaged infrastructure that would eventually link it to Xiamen, Fujian province.

Besides the massive economic costs associated with building a bridge or tunnel across the Taiwan Strait, security concerns, geologic vulnerabilities (due to earthquakes) and the sheer width of the strait present technical challenges to its construction. Even if the infrastructure were built, it is not clear that they would be economically justifiable given that airliners and ships are now allowed to travel across the strait frequently.

For decades, China and Taiwan had no official interaction at all, and infrastructure linking the two was something only Beijing wanted. Taipei viewed any bridge or tunnel link as a potential security liability, since it could enable easier access to the island by mainland military forces in times of crisis. While tensions have thawed in recent years, talks between the two sides still only involve economic and cultural issues, not political issues. Combined with logistical challenges, the absence of direct relations between the two makes it extremely unlikely that the infrastructure will built any time soon.

Though a bridge or tunnel link remains largely illusory, Beijing’s hope to bridge the gap — both physically and symbolically — across the Taiwan Strait was brought a bit closer to reality in early July, when Beijing and Taipei finalized a plan to supply water from the mainland to Kinmen, an outlying Taiwanese island less than 3 kilometers from the coast at Fujian. Under the plan, which was long opposed by Taipei and took 10 years of negotiations to resolve, water would be sent from Fujian province to Kinmen at its narrowest point.

To alleviate the island’s lingering water shortage, two possible pipeline routes were proposed, one involving a 26.8-kilometer pipeline directing water from Jinji reservoir in Fujian’s Jinjiang to Kinmen, and one involving a 30 kilometer-long pipeline, nearly 9 kilometers of which would be undersea, connecting the Jiulong River in Xiamen and the city’s Tingxi reservoir. (The latter was the preferred route.) This water pipeline would be the first cross-strait infrastructure link. Significantly, China has pursued the project even though Fujian province itself is suffering from a lingering water shortage, making clear how strategically important Beijing views a physical link with Taiwan. During negotiations, discussions resurfaced of constructing a bridge between Kinmen and Xiamen.

Compared to the much more ambitious proposal to link the mainland to Taiwan via bridge or tunnel, the pipeline with Kinmen is not in itself very significant. However, it does offer an example of Beijing sacrificing what is superficially pragmatic for the sake of its strategic goals. In particular, Kinmen had once been the leading military frontier until the end of cross-strait military standoff in 1992, and Beijing believes that assisting the island can offer an example of cross-strait integration. Beijing also believes it could allow more Taiwanese residents to benefit from growing economic interaction with China without undermining Taipei’s political independence.

Symbolic Steps

Warming cross-strait ties have coincided, and indeed complemented, China’s attempt to project economic influence externally, including with Taiwan. Coupled with Beijing’s vastly superior military capabilities, the economic incentives for cross-strait cooperation have formed the backbone of its less overtly aggressive stance toward the island in the past decade. While reunification remains the ultimate goal, it has been widely acknowledged among Beijing’s political elites that, as long as the possibility of peaceful reunification remains, there is little urgency or strategic necessity in forcing a final resolution unless a serious crisis emerges between Taiwan and China.

Instead, Beijing is focusing on a more conciliatory approach to reinforce the concept of interdependence and prevent Taiwan from distancing itself from the mainland economically and politically. At least for now, Taipei appears to have reconciled this approach with its own so-called “economic first, politics later” strategy toward the mainland. This strategy allows it to benefit from economic cooperation with China and create a relatively calm environment that would benefit Taipei’s development without threatening its independent identity.

Beijing’s emphasis on interdependence has some merit, too. Over the years, China has benefited from easing restrictions on commerce and cultural exchanges with Taiwan, along with Taiwanese investment that has helped it upgrade its industrial sector. A less hostile government in Taipei has also been important for Beijing’s political legitimacy internationally. Moreover, China allowed a much more open market and more preferential trade and investment policies to Taiwan than the island nation would find elsewhere. Currently, trade with China and Hong Kong accounts for nearly a third of Taiwan’s economy, in part helping the island avoid further decline amid the global slowdown.

Since reunification is always going to be an imperative for Beijing until it actually takes place, the proposed infrastructure is an important step symbolically for its integration strategy. Trade patterns can change rapidly, and interests there can shift — especially now that the Chinese economy itself is undergoing massive internal changes. Consequently, a pipeline or tunnel may not be especially important in themselves and may even be unrealistic and impractical, but taken with the other developments, they point to a new type of strategic thinking in Beijing.

“China’s Hopes for Bridging the Taiwan Strait is republished with permission of Stratfor.”