Paul Krugman claims that he only reads other liberals, because conservatives have nothing to offer. I’m sure that makes life less aggravating, but unfortunately living in a bubble can lead to a false sense of security that you are “always right” about everything. One area where Krugman has been consistently wrong is fiscal policy, where he keeps citing studies that don’t show what he thinks they show. They fail to account for monetary offset. For instance they might look at differing fiscal policies among American states.

I’ve talked about this problem many times, but Mark Sadowski left a comment in an earlier post that puts meat on the bone, with a regression showing no significant fiscal multiplier, even using Krugman’s preferred data set (but also accounting for monetary offset.) Here is Mark’s comment:

Scott,

Krugman’s latest:http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/10/15/five-on-the-floor/

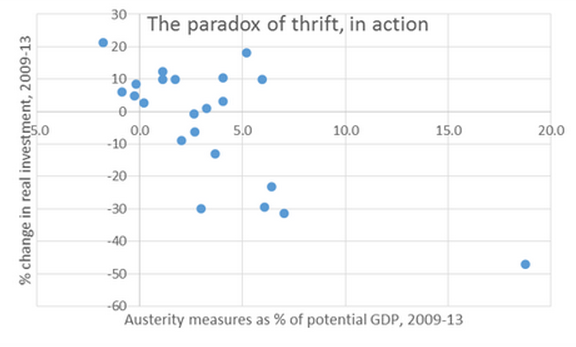

“…What’s more, the turn to austerity that began in 2010 gives us an opportunity to observe the paradox in action. Take the estimates of fiscal contraction 2009-13 from the IMF Fiscal Monitor in fall 2012 (Figure 13), and compare this with changes in real fixed investment over the same period (from Eurostat). It looks like this:

That’s Greece in the lower right corner, of course — but even without Greece there’s a clear negative correlation between government austerity and investment. Yes, you can try to explain away the results with endogeneity, but it’s a strain.This is prima facie evidence of crowding-out in reverse, aka the paradox of thrift…”

Krugman defines the degree of fiscal contraction as the change in the general government cyclically adjusted primary balance as a percent of potential GDP between 2009 and 2013. He graphs this for 22 nations. These consist of all of the eurozone members except Cyprus, Estonia, Luxembourg and Malta, plus Denmark, the Czech Republic, Sweden, the UK, Norway, Switzerland, Iceland, Japan and the US. (Krugman doesn’t explicitly say which nations, but it is clear if you read between the lines.)

Right away you should see the problem. Thirteen of these countries are eurozone members, and another (Denmark) is pegged to the euro. Thus two thirds of the sample have the same exact monetary policy. It would be very surprising if there were no correlation between the degree of fiscal austerity and the change in real gross fixed investment.

I’ve run regressions using the exact same investment data and the change in the cyclically adjusted primary balance between 2009 and 2013 from the October 2013 IMF Fiscal Monitor. The correlation is statistically significant with the R-squared value equal to 52%. When you run the same regression on just the 13 eurozone members and Denmark the R-squared value rises to 71%. But when you run it on the other eight nations plus the eurozone as a whole, the result is not statistically significant and the R-squared value drops to only 8%.

In particular, four nations out of the original 22 nation sample had above average fiscal austerity and investment growth, namely Iceland, Slovakia, the UK and he US. I have no idea what’s going on in Slovakia, but the UK and the US have both done significant amounts of QE, and Iceland is Krugman’s poster child for the benefits of currency devaluation in his never ending feud with the Council on Foreign Relations.

PS. Some have noticed a recent increase in typos. I recently began using Dragon Dictate (as I got sick of typing 6000 pages using two fingers), and it doesn’t always print out what I am trying to say. For instance, Dragon believes “been burning key” is the current Fed chair. Look for “Janet’s yelling” in future posts. However I am a rather poor speller, so there is poetic justice in this. Spell check had been making me seem slightly less inept than I really am. IT giveth, and IT taketh away. Just read my posts phonetically.

Update: Krugman is certainly right about this:

I’m coming to this a bit late, but I see that there’s now extensive evidencethat facts not only don’t win arguments, they make people on the wrong side dig in even deeper: “When your deepest convictions are challenged by contradictory evidence, your beliefs get stronger.”