The longer you are involved with the financial markets, the more you respect the market’s obsession with the Fed. The quantitative easing process (QE) pumps money into the global financial system. The money can find a home in stocks, real estate, gold, etc. Handicapping the Fed is a big part of successfully navigating through the financial market waters. Therefore, it is prudent to understand what drives the QE decision making process at the Federal Reserve.

Primary Fed Objectives

The Federal Reserve Act was altered by Congress in 1997 adding the “dual mandate” clause:

“The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Open Market Committee shall maintain long run growth of the monetary and credit aggregates commensurate with the economy’s long run potential to increase production, so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices and moderate long-term interest rates.”

The Fed’s dual mandate in short form is “maximum employment and stable prices”. Stable prices speak to low inflation.

How Are They Doing With Maximum Employment?

The chart below is posted on the website of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. It shows the unemployment rate dating back to 2002. The current unemployment rate is higher than it was at any point between 2003 and early-2008, meaning unemployment remains high relative to recent historical standards.

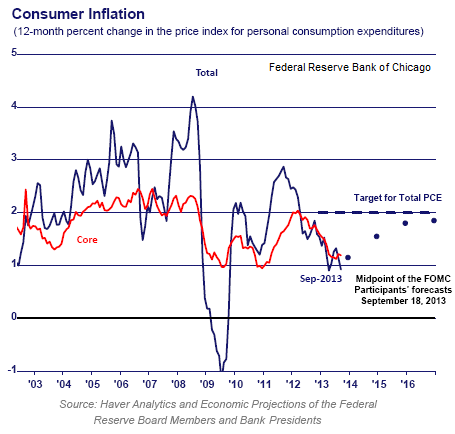

How About Inflation?

From a distance, it may seem as if no inflation would be the best case scenario. That is not the case in the central bank world in which we live. Central bankers have nightmares about Japan-like deflationary spirals. A deflationary spiral occurs when prices are falling and consumers sit on their wallets hoping for a better deal. As they wait, prices fall even further, creating a negative economic feedback loop. Falling prices can disrupt the balance between assets and liabilities, which in turn speaks to credit worthiness and solvency. Therefore, central bankers prefer to see annual inflation running closer to 2%, rather than 0%. The chart below shows inflation continues to hover near levels that make central bankers worried about slipping into deflation.

Why Taper Then?

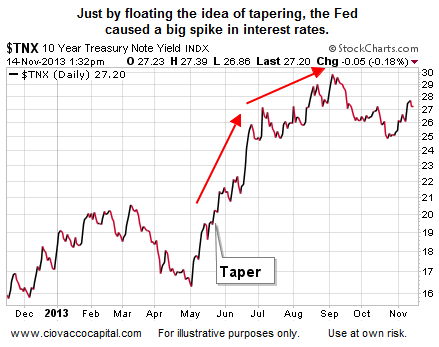

If the Fed is failing to meet the mandated maximum employment target and inflation, if anything, is too low, why would the Fed cut back on QE? The answers: fear of asset bubbles and fear of a rapid spike in interest rates. Interest rates have been and are being artificially held down via the Fed’s QE-induced demand for Treasuries (TLT). The Fed caught a glimpse of just how difficult it will be to taper their way out of the QE business earlier this year. In late May, during a Q&A session Ben Bernanke said it was possible the Fed would begin reducing their monthly bond purchases (taper) before the end of the year. Interest rates spiked on the news, which is exactly what the Fed wants to avoid. If you want to see what can happen when rates spike, review 1994.

Investment Implications – Fed Bias Remains Bullish

The near-impossible challenge of unwinding a massive balance sheet without disrupting the financial markets awaits the Fed. The only real out the Fed has is a strong economy. If the economy strengthens to a point where it can tolerate higher interest rates, the Fed has some hope of tapering without a massive negative impact on the financial system.

How does all this help us now? We know tapering will not come in the short-run based on employment or inflation figures. When handicapping Thursday’s Yellen hearing, PIMCO’s Mohamed A. El-Erian summarized a reasonable expectation for the Fed’s bias going forward. From CNBC:

Look for Thursday’s hearing to signal that, despite imperfect policy tools, the Fed is committed to keeping its foot on the accelerator even though outcomes may well continue to fall short of expectations, and even though the “costs and risks” are likely to rise. If it ends up making a mistake, something that it will try very hard to avoid, it would likely be one of excessive accommodation rather than premature tightening.

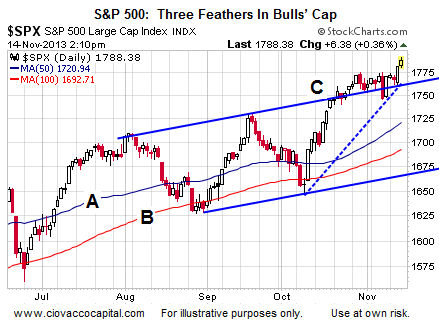

We agree with PIMCO that erring on the taper-too-late end of the spectrum fits with central bank tendencies. If concerns about Fed policy begin to negatively impact the market’s tolerance for risk, it will show up in the observable evidence tracked by our market model. Two examples of observable (and unbiased) evidence are the slopes of the moving averages in the chart below. Traders use the slope of the 50-day moving average (see A below) to monitor the health of the intermediate-term trend. The slope of the 200-day moving average (point B) is used to monitor the long-term trend. When the slopes are positive, it indicates a bullish bias. The S&P 500’s breakout near point C is classified as anecdotal bullish evidence since the trendline was drawn manually, which opens the door to personal bias. Our market model uses A and B, but not C.

As of this writing, the observable evidence continues to align with “risk-on” and the expectation that a major Fed taper is not imminent. Therefore, we will continue to hold our positions in U.S. stocks (VTI), technology (QQQ), energy (XLE), financials (XLF), small caps (IWM), foreign stocks (VEU), and emerging markets (EEM). As we noted on November 12, we would like to see some improvement in emerging markets. Should EEM remain weak, we may reduce our exposure for a second time before the markets close this Friday.