Saturos sent me some interesting PowerPoint slides by Paul Krugman:

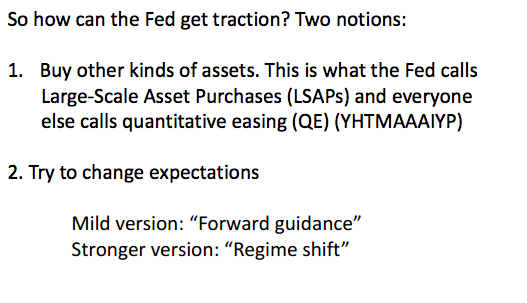

Krugman overlooks a third option, targeting an alternative variable that is not subject to the zero lower bound. Or perhaps he regards that as a regime change. I can’t be sure. But it need not involve the Fed changing its inflation/unemployment targets, so it depends how one defines ‘regime.’ I believe he regards “regime shift” as something like an increase in the inflation target to 4%.

Krugman overlooks a third option, targeting an alternative variable that is not subject to the zero lower bound. Or perhaps he regards that as a regime change. I can’t be sure. But it need not involve the Fed changing its inflation/unemployment targets, so it depends how one defines ‘regime.’ I believe he regards “regime shift” as something like an increase in the inflation target to 4%.

In any case, alternative targets include foreign exchange rates, the price of actively traded commodities such as gold, and CPI/NGDP futures prices. Fisher’s Compensated Dollar plan was an adjustable gold price peg, aimed at stabilizing the price level.

In the past I’ve argued that Krugman had a sort of blind spot in this area. For instance, he was too pessimistic about the ability of the Swiss National Bank to peg the franc at a lower level vs. the euro. In any case, it’s interesting to compare these schemes to forward guidance. Krugman correctly points out that there is a theoretical possibility of an “expectations trap” with forward guidance. Markets might not believe central bank promises to fully carry through with monetary stimulus, as the initial effect on expectations is all the central bank really wants and needs.

You can think of the alternatives to interest rate targeting (assets that lack a zero bound) as a way of overcoming the expectations trap. When you target a variable with no zero bound (forex, gold, NGDP futures, etc) you are forced by the market to do “enough” to make the promise credible. Hence no expectations trap. In this post Krugman correctly pointed out that the risk of an expectations trap is replaced with the risk of a central bank balance sheet that is bloated to undesirable levels. In practice, I think that’s unlikely to be a problem for any “reasonable” nominal aggregate policy goal. And if it does become a problem the market is telling you that perhaps your inflation/NGDP target path is too low.

And we should not overlook the bright side of a bloated balance sheet. Suppose Japan was still at the zero rate bound after pegging CPI futures at a 2% premium over the spot CPI. That might imply a bloated BOJ balance sheet. But that would prove beyond any doubt that the Japanese government had just spent the past 20 walking down a sidewalk covered with $100 bills (or 10,000 yen bills) without once stopping to pick one up. Not smart, and it’s about time they raised their inflation rate target if they can do so without raising the nominal cost of funding the Japanese debt by one iota. A free bento box.

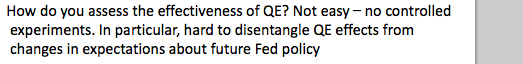

Krugman also makes this comment:

Once again, this is correct but slightly misleading. The distinction between the direct effect of a policy shift and the effect of a shift in the future expected path of policy is almost equally important when not at the zero bound. Any monetarist thought experiment involving a higher money supply ALWAYS involves the implicit assumption that the increase is permanent, or at least semi-permanent. Alternatively, when markets react very strongly to changes in the fed funs target (Jan. 2001, Sept. 2007, Dec. 2007) the market reaction almost certainly reflects changes in the expected future path of the fed funds rate, not the current setting.

Once again, this is correct but slightly misleading. The distinction between the direct effect of a policy shift and the effect of a shift in the future expected path of policy is almost equally important when not at the zero bound. Any monetarist thought experiment involving a higher money supply ALWAYS involves the implicit assumption that the increase is permanent, or at least semi-permanent. Alternatively, when markets react very strongly to changes in the fed funs target (Jan. 2001, Sept. 2007, Dec. 2007) the market reaction almost certainly reflects changes in the expected future path of the fed funds rate, not the current setting.

I was also amused by this; from one of his PP slides:

I wondered what had been deleted from this passage, as there seemed to be missing material at the end of each line. Here’s where Google is a miracle of the modern world—I was able to find the Wikipedia source:

I wondered what had been deleted from this passage, as there seemed to be missing material at the end of each line. Here’s where Google is a miracle of the modern world—I was able to find the Wikipedia source:

On September 13, 2012, the Federal Reserve announced a third round of quantitative easing (QE3).[7] This new round of quantitative easing provided for an open-ended commitment to purchase $40 billion agency mortgage-backed securities per month until the labor market improves “substantially”. Some economists believe that Scott Sumner‘s blog[8] on nominal income targeting played a role in popularizing the “wonky, once-eccentric policy” of “unlimited QE”.[9]

Ah, that’s much better!