In the first three posts of the series I sketched out a simple model of inflation and NGDP growth. For large persistent changes in the money supply, M dominates everything else. But inflation reflects both money growth and changes in the real demand for money. So real GDP growth raises real money demand, and hence is deflationary, while higher nominal interest rates reduce real money demand, and hence are inflationary. The later point is not just NeoFisherism; higher interest rates actually cause inflation to be higher than what you’d get from money growth alone. All my claims so far are supported by literally hundreds of money demand studies done in the 1970s and 1980s. This stuff is not controversial for monetary economists who recall the 1970s.

Here in the final post I’ll consider the money/inflation correlation you’d expect when the money growth rate is endogenous. I’ll start with the case of Bretton Woods, which covers the first part of the period in Barro’s table. Speaking of which, I erred in saying Barro used the monetary base; he actually used the currency stock. But I’m quite confident that this distinction was unimportant for the period covered. (Today it would be very important.) I also discovered that he got the data from the IMF. Still not sure if he used differences of logs.

Under Bretton Woods, exchange rates were fixed and this tended to equalize inflation, due to Purchasing Power Parity. But inflation rates were not completely equalized, as the real exchange rates would change over time, due to factors such as the Balassa-Samuelson effect. There would also be gaps between money and inflation, due to differing patterns of real GDP growth and velocity growth. And here’s the key point—there’s no logical reason to expect changes in real exchange rates to be strongly correlated with variations in money growth caused by all sorts of other factors. This means that under Bretton Woods, the variation in inflation rates (which is identical to the variation in real exchange rates) will not be closely correlated with variations in money growth rates.

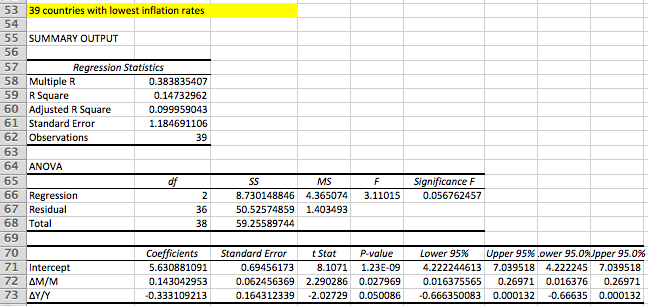

I had Patrick Horan do separate regressions for the top and bottom half of the data set, the 40 countries with the highest inflation rates and the 39 with the lowest. The top half regression had an R2 of over 98%. But here’s what he found in the bottom half:

A very low adjusted R2, below 10%. About the best you can say is that the coefficients have the correct sign.

A very low adjusted R2, below 10%. About the best you can say is that the coefficients have the correct sign.

And the problem isn’t just Bretton Woods, the same thing happens under inflation targeting. If everyone is targeting inflation at 2%, then any variation in inflation will simply represent central bank errors, and will likely not be strongly correlated with variation in money growth rates.

But don’t be fooled by the endogenous money correlations, or lack thereof. Money growth is still driving inflation and NGDP; it’s just that the need to hit certain inflation/exchange rate targets is driving money growth. If a country had decided to have 5% faster money growth, on average, then they would have had to leave Bretton Woods, and they would have had roughly 5% higher inflation and NGDP growth, on average.

Thus the entire “endogenous money” issue is often misunderstood. It doesn’t mean that money growth is unimportant; it just means that if you are targeting something other than money, then money growth is determined by your target. In other words, don’t say, “money growth didn’t cause X, as it’s endogenous”. Your interest rate, or exchange rate, or inflation target caused money growth to cause X. Money growth is still the “real thing”, even if you don’t see it in sophisticated models by Michael Woodford.

Conclusion: A monetarist model that tries to explain NGDP growth and inflation by looking at money growth, real GDP growth and the opportunity cost of holding money does an excellent job of explaining the stylized facts of the Great Inflation, when there was enormous variation in inflation and NGDP growth. And it does so in a way consistent with basic economic theory about how people behave, how they react to changes in the costs and benefits of holding real cash balances. As far as I know, no other model can explain all of these stylized facts. Indeed no other model comes close. I’ll gladly convert to New Keynesianism or Austrianism, or Old Keynesianism, or MMTism, or Marxism, or New Classical economics, or RBC, or any other school of thought, if you can provide a coherent theoretical explanation for these stylized facts. And if not, then please tell my why I shouldn’t keep on being a market monetarist. I’ve got a model that works; why give it up for one that doesn’t?