When historians sort out this era of once-a-decade financial bubbles, they’ll marvel at how dissimilar the drivers of each boom were. The junk bonds of the 1980s were essentially leveraged tools for extracting wealth from companies. The dot-coms of the 1990s were vehicles for exotic new technologies and untested business models. The sub-prime mortgages and credit default swaps of the 2000s were semi-fraudulent fee-generation schemes.

All, in retrospect, were strange, unsteady foundations on which to build a global economy. But they look positively sane compared to the pillars of the current expansion: China and fracking.

As the true extent of China’s debt binge becomes apparent, the only reasonable reaction is awe. To cook the story down to its essence, the world’s biggest developing country decided to become developed in the space of a few years, borrowing nearly as much money as the entire rest of the world and using the proceeds to buy up every conceivable kind of industrial commodity. The result was a natural resources boom that, for a little while, floated the global economy on a rising tide of leverage. For much more detail, see this long Zero Hedge analysis.

Then, as all debt binges eventually do, this one ended in a tangle of malinvestment and evaporating cash flows. China’s excess capacity in basic industries like steel and cement is now epic. Mass layoffs are being announced daily. Its velocity of money — a measure of the tempo of economic activity — is the lowest in the world. And external trade is collapsing, with February imports and exports falling 13.8% and 25.4%, respectively.

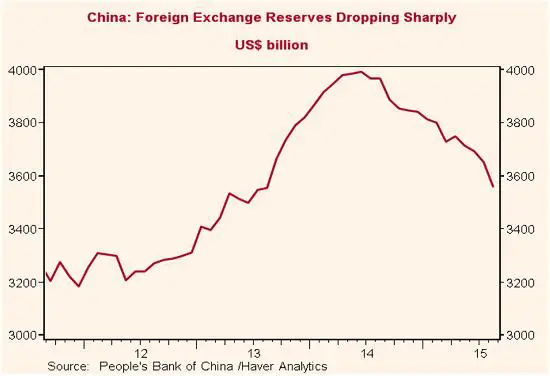

Now in damage control mode, China is spending its foreign exchange reserves in a probably-futile attempt to keep its currency from plunging, while capital is pouring out of the country in search of safe havens and hedge funds are placing billion-dollar bets on a big yuan devaluation.

China, in short, has become a drag on the global economy rather than its savior. And much, much worse is coming.

Now on to fracking, which involves pumping toxic industrial chemicals into the ground to free up hard-to-reach oil and gas reserves. For a while, this was the Internet of the energy business, captivating bankers and entrepreneurs and igniting a scramble for prime drilling rights.

Between 2006 and 2014, US natural gas production rose from 64 billion cubic feet a day to 90 billion while oil production rose from 5 million barrels a day 9 million. Along the way, fracking produced millions of well-paying jobs, lifting whole US regions from bust to boom and generating massive tax windfalls for favored states.

But this too was a leveraged mirage. The surge in supply swamped a global market that was already slowing due to China’s bursting credit bubble. The result was a crash in oil and gas prices and a bloodbath in the US oil patch.

All those now-idle rigs cost someone a lot of money, much of it borrowed from banks and junk bond investors. So unless oil and gas return to 2012 levels in short order, the year ahead will see a rolling wave of bankruptcies and huge write-offs for lenders, pension funds and yield-seeking retirees. All of which, like China, constitute a drag on growth.

In a system that seems incapable of functioning in the absence of bubbles, the question now becomes: What can the monetary authorities convert into the next bubble? And the answer is not at all clear. A case can be made that the rush into negative-coupon German and Japanese bonds is bubble-like. But this doesn’t seem to be generating jobs or income for anyone — just the opposite. Buying a negative interest rate bond is a bet on shrinking capital.

In the US, cars were hot for a while but subprime auto lending is already hitting a wall and will likely go the way of China and fracking in the year ahead. Solar power? Maybe, but growth there comes at the expense of coal and natural gas, so it’s a wash in the short run. Finance? Forget it. Negative interest rates are an existential threat to traditional lending, and the big banks are all retrenching. Government funded infrastructure? That’s a liberal politician’s dream, but it sounds a lot like what China just did, and bubbles tend not to repeat in this way.

The terrifying conclusion is that other than a major war, there’s nothing out there capable of generating another global bubble. And absent another bubble, there’s nothing between us and the abyss.