There are two possible correlations between currency values and exchange rates:

1. The SE Asian model (1997): The forex value of the domestic currency and the equity market are positively correlated. Financial crisis leads to both currency depreciation and plunging equity prices.

2. The Japanese model: The forex value of the domestic currency is negatively related to equity prices, as tight money leads to a rising exchange rate and a falling stock market.

The US followed the SE Asian model in the late 1990s, as the high tech boom pushed up both the dollar and stock prices. In late 2008 and in 1931-32, the US followed the Japan model, as tight money caused the dollar to appreciate and the stock market to fall. (Just one more example of NRFPC)

I’ve been puzzled about China’s exchange rate. In August 11-13, 2015, a 3% yuan devaluation seemed to depress stock prices, and a much smaller example of the same phenomenon occurred during January 6-8, 2016. That seems like the SE Asian model. But I would have expected China to follow the Japan model, as they currently need to stimulate AD in the economy. And other Chinese stimulus measures do seem to push stock prices higher.

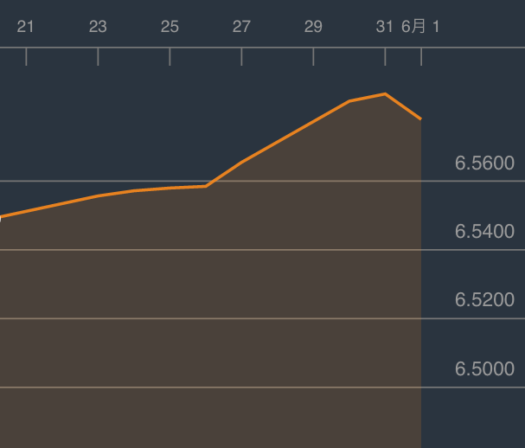

To make things even more confusing, in the past week China seems to have suddenly flipped to the Japanese model. Tyler Cowen reports that there’s been a lot of recent concern about the value of the yuan, which has recently plunged close to the lowest level in years. And yet Hong Kong stocks seem to be negatively correlated with the yuan, unlike August 2015 or early 2016 (graph actually shows inverse of yuan):

Not a large depreciation, but the yuan has been falling for several weeks, and this represents a pretty significant move, by Chinese standards.

Not a large depreciation, but the yuan has been falling for several weeks, and this represents a pretty significant move, by Chinese standards.

Notice that Hong Kong stocks show a “Japan type” correlation over the past week:

Here’s my best guess as to what’s going on here. If you look at the two previous currency moves, they occurred in the midst of a much longer and sharper fall in equity prices, suggesting that currency depreciation was not the only causal factor. More likely, equity markets were falling on fears of financial/macroeconomic problems in China, and the exchange rate was reacting to those fears. Admittedly the rate is controlled by the government, but markets may have seen the sudden move in August as a sign that things were worse in China than they thought. I actually don’t like that sort of (ad hoc) explanation, but I can’t think of anything better.

In contrast, over the past week markets may be reacting to the fall in the yuan as a much needed monetary stimulus. However I’m not at all confident that the correlation won’t revert back to the patter on late 2015. I’m still puzzled.

There are basically two ways to stimulate the Chinese economy:

1. Debt—which leads to major misallocation of resources and fiscal problems down the road when the Chinese government has to bail out the banks and or SOEs

2. Monetary stimulus, which helps the more efficient private sector in China.

The beauty of monetary stimulus is that it makes the process of creative destruction less painful. China is currently seeing a boom in tourism far beyond anything the world has ever seen. The Chinese government estimates that this will create another 12 million jobs for the Chinese poor. At the same time, millions of jobs will be lost in the old “rustbelt” of north China, where steel mills and coal mines will need to be shut down. Currency depreciation caused by monetary stimulus makes that transformation easier, whereas more debt simply causes the SOEs to double down on their failed policies of too much investment in heavy industry.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again. China needs easier money (more NGDP) and tighter credit (less moral hazard.) It’s that simple. But obviously hard to do in practice, given the political muscle of Chinese borrowers.

PS. I don’t know which stock market is best. The HK market is viewed as more efficient, and better correlated with macro conditions in China. The Shanghai market is occasionally manipulated by the government, and has lots of SOEs that might be hurt by a weaker yuan, as they have dollar denominated debts. On the other hand, a weaker yuan might hurt Hong Kong, as its currency would then become more overvalued.

PPS. Here’s the yuan over a longer period of time (again inverted):