By Lance Roberts, StreetTalk Advisors

I recently posted two pieces discussing that the peak of economic growth was likely behind us. (See here and here) In particular both pieces addressed personal consumption expenditures and their importance to the overall strength and direction of the economy. To wit:

“…personal consumption expenditures (PCE) comprise about 70% of the gross domestic product calculation. As PCE goes – so goes the economy.”

The importance of consumption on the overall economy should not be overlooked. While, in the economic cycle, it is production that comes first, as it provides the income necessary for individuals to consume, it is ultimately consumption that completes the cycle by creating the demand. This is the problem that government, and the Fed, face today.

Despite repeated bailouts, programs, and interventions – economic growth remains mired a sub-par rates as consumers struggle in a low growth/high unemployment economy. Businesses, which have been pressured by poor sales, higher taxes and increased government regulations, have learned to do more with less. Higher productivity has lead to less employment and higher levels of profits.

The dark side of that equation is that less employment means higher competition for jobs which suppresses wage growth. Lower wage growth and incomes means less consumption which reduces the aggregrate end demand. In turn, lower demand for products and services puts businesses on the defensive to “do more with less” in order to protect profit margins. Wash, rinse and repeat. This is why deflationary economic environments are so greatly feared by the Fed as that virtual spiral, between production and consumption, is incredibly difficult to break.

This brings us to the latest report from Goldman Sachs entitled “The Consumption Setback” (via Zero Hedge) which discusses the reality that consumer is slowing down which will likely have a negative impact on future growth. This is a fairly sharp turn from their previous stance of an economic comeback in 2013 which I have previously argued heavily against.

A Consumption Setback

Coming into this year, we expected a notable slowdown in real personal consumption expenditures (PCE) from around 2% in 2012 to a 1% (annualized) pace in the first quarter of 2013. The main reason was the hit to disposable income resulting from the 2-point increase in payroll taxes that took effect in January. Based on our statistical analysis of the effects of past shocks to disposable income, we thought that the tax increase would deliver a sizable, front-loaded hit to spending. Such a front-loaded hit also seemed plausible intuitively. After all, lower- and middle-income consumers–many of whom seem to spend their income on a pay-as-you-go basis and should therefore respond quickly to a shock–saw a reduction in their disposable income of up to 2%.

This forecast was too pessimistic. Our current estimate is that real PCE grew 2-1/2% (annualized) in the first quarter, which would be the strongest quarter in two years. While this estimate is based on incomplete data for March and the January/February data are subject to revision, the basic thrust is unlikely to change at this point in the quarter. We have therefore been wondering whether we have already moved “over the hump” of fiscal contraction, at least as far as the consumer is concerned.

But the recent data suggest that the answer is no:

1. Weaker tracking. The March retail sales report showed a drop in “core” sales (excluding autos, building materials, and gasoline) to a level below the first-quarter average. If core retail spending through the quarter (that is, June vs. March) grows at the 2% pace seen over the prior year, quarterly average growth in core spending as well as real PCE (that is, the Q2 average vs. the Q1 average) could be as low as 1%. Admittedly, the retail sales data can be noisy and the weak March reading might have been influenced by seasonal adjustment distortions related to the timing of Easter and/or the relatively poor weather. But we do need a significant rebound in the pace of growth over the next few months to avoid a meaningful deceleration in Q2.

2. Weaker confidence. The weaker data are not confined to the retail sales release. Consumer sentiment according to the University of Michigan also took a dive in early April. To be sure, the preliminary Michigan reading is based on a small sample of households and other surveys such as the daily Rasmussen Reports series do not show a meaningful decline. But we would put a bit of weight on the Michigan reading given its relatively good historical performance as a coincident indicator of spending.

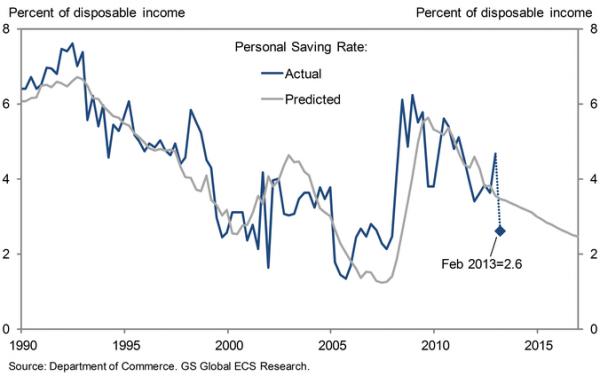

3. Lower saving rate. According to the February personal income and spending release, the personal saving rate currently stands at 2.6%. Except for the January 2013 reading, which was artificially depressed by tax-related income shifting between 2012 and 2013, this is the lowest number since late 2007. As shown in Exhibit 1, it is nearly 1 percentage point below our estimated equilibrium, which is based on a model using household wealth, bank lending standards, and labor market conditions. If this model is correct, we might see upward pressure on saving and correspondingly weaker growth in spending over the next couple of quarters.

Exhibit 1: Savings Rate Below Equilibrium

In our view, the most plausible interpretation of the weaker data is a delayed negative impact from the tax hike. Although we find a front-loaded impact more intuitive given the concentration of the hit among pay-as-you-go consumers, some of the models we estimated–specifically those using the Romer-Romer measure of tax shocks–do show a significant amount of back-loading. The low saving rate also points in that direction.

Assuming that much of the impact of the tax hike really is indeed still “in the pipeline,” we could see a period of weakness in consumer spending. One way to get a sense of this is to assume that the gap between the personal saving rate and our estimate of the equilibrium rate will gradually disappear over the next 6-9 months. This would mean that the saving rate would need to rise by an average of 0.1 point per month, which would mechanically subtract 1.2 percentage points from annualized consumption growth. If real income grows 2-1/2%, this would mean real consumption growth of 1% to 1-1/2%. Combined with the likely weakness in federal spending, slow consumption growth would make it difficult for real GDP to grow much more than 2%, even if homebuilding and business investment continue to grow at healthy rates, as we expect. This reinforces our view that GDP growth in 2013 will still be relatively sluggish, with only a modest pickup late in the year.”

Of course, it isn’t just Goldman Sachs downgrading their outlook but also Bank of America as economist Hans Mikkselsen penned:

We continue to side with the weakening macro backdrop and retain our tactical (short-term) short positioning in investment grade credit. Perhaps stocks and credit are holding up on the perception that US and Japanese QE will push investors into US risk assets regardless of fundamental weakness – in other words, that strong technicals will overcome weak fundamentals.

That appears uncharted territory, as what we have seen in the past is that QE can work to push investors into risk assets when perceived to boost economic activity and thus create inflation. We have little evidence that QE alone can do the job, without being perceived to improve fundamentals. Thus, again, we expect the weakening macro backdrop to prevail…Perhaps the US economy is strong enough to overcome the recent adversities.

This argument is close to our view and consistent with consensus expecting a rebound in the economy in the second half of the year. However, the current slowdown in the economy is clearly worse than expected at this stage…Moreover, on top of surprising domestic weakness we are faced with a number of important external risks such as those emanating from North Korea and Europe. Thus if stocks and credit are counting on the economy to pull through the near-term challenges they must believe strongly in an underlying more independent source of growth – such as the housing market recovery.”

The importance of this analysis is that the mainstream analysts, and economists, are now having to come to grips with the fact that, as we have been continuously discussing since early 2011, the economic data doesn’t support the stock market valuations at these levels. At some point, despite the ongoing interventions by the Federal Reserve, the stock market will revert to the underlying fundamental story which has been slowly deteriorating over time.

The difference between my view and that of Jan Hatzius, and most other economists, is that the current slowdown is not just a “soft patch” but the end of the expansionary cycle that began in 2009. That belief is simply based on the fact that economies do not grow indefinitely but cycle between expansions and contractions. In the current economic environment, where the consumer is caught in a balance sheet deleveraging cycle, economic contractions occur more frequently than they do under more normal economic conditions. This is not an indictment of fiscal, or monetary, policies but simply a statement about the cycles of an economy.

The question that remains to be answered is simply how long can the Fed’s artificial intervention programs continue to elevate asset prices? Unfortunately, no one really knows the answer. However, we do know that the during “normal” economic contractions the markets correct on average by roughly 30%. Since the current elevation in asset prices has not been due to improving fundamentals but rather artificial inflation – it is likely the next correction in the markets, and the economy, will be anything but normal.

The post Goldman Sachs: A Consumption Setback appeared first on PRAGMATIC CAPITALISM.