Inquiring minds are reading the San Francisco Fed Economic Letter “Why Are Housing Inventories Low?”

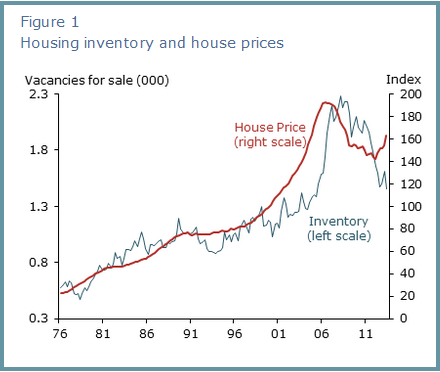

Inventories of homes for sale have been slow to bounce back since the 2007–09 recession, despite steady house price appreciation since January 2012. One probable reason why many homeowners are not putting their homes on the market is that their properties may still be worth less than the value of their mortgages, which would leave them owing additional money after a sale. In other cases, homeowners may simply be hoping that house prices will continue to rise, allowing them to recover lost equity.

No matter what the condition of the economy might be, some base level of inventory for sale always exists in the housing market. Young homeowners may sell their homes in order to relocate for a job or because their family has gotten larger and they need more space. Older homeowners may sell because they no longer need so much space or they want to turn their housing investment into cash as they reach retirement. All these reasons for selling can be thought of as life-cycle motives not necessarily tied to the business cycle. Such noncyclical factors produce a general level of churning in the housing market. Nevertheless, inventories show a distinct cyclical pattern, rising in good times and falling in bad times. This could be due to the cyclical nature of credit conditions. The risk premiums charged by lenders and their willingness to accept loan applications tend to ease during good economic times, allowing more potential buyers to enter the market. At the same time though, the level of house prices is by far the most important cyclical variable that influences the inventory of homes for sale.

No matter what the condition of the economy might be, some base level of inventory for sale always exists in the housing market. Young homeowners may sell their homes in order to relocate for a job or because their family has gotten larger and they need more space. Older homeowners may sell because they no longer need so much space or they want to turn their housing investment into cash as they reach retirement. All these reasons for selling can be thought of as life-cycle motives not necessarily tied to the business cycle. Such noncyclical factors produce a general level of churning in the housing market. Nevertheless, inventories show a distinct cyclical pattern, rising in good times and falling in bad times. This could be due to the cyclical nature of credit conditions. The risk premiums charged by lenders and their willingness to accept loan applications tend to ease during good economic times, allowing more potential buyers to enter the market. At the same time though, the level of house prices is by far the most important cyclical variable that influences the inventory of homes for sale.

Two important points emerge from Figure 2. First, in the aggregate U.S. data, the for-rent inventory of homes as a share of total housing units has risen steadily during the recession and the recovery, while the for-sale inventory has steadily dropped and is now stabilizing.

The data do not extend far enough back to indicate whether this is typical over the economic cycle. But other sources, such as Census Bureau aggregate inventory data, suggest that the drop in owner-occupied units relative to renter-occupied units is unprecedented since the 1960s. This phenomenon is widespread. The surge in foreclosures during the housing bust cannot be the only cause of this shift.

In theory, falling house prices alone may keep some homeowners from selling. It may seem logical that decisions to sell should be based only on information about current and future market conditions. But David Genesove and Christopher Mayer (1997) show that homeowners take more time to sell their houses if prices have fallen since the original purchase. That is, two similar homeowners experiencing similar housing market conditions will behave differently if one of those homeowners has an unrealized loss on his or her house.

Another possible explanation for the breakdown in the normal relationship between prices and inventories of homes for sale is that homeowners may be taking a longer-term view of the housing market. It is well documented that house price changes are persistent, meaning that price rises are likely to be followed by more rises, and price drops by more drops. Homeowners with flexibility on the timing of their home sales can potentially take advantage of this persistence. If they observe prices going up, they may want to wait and gamble that the increases will continue, allowing them to sell later at a higher price.

The data are consistent with this explanation. Figure 4 confirms on a county level the negative relationship between prices and inventories shown at the aggregate level in Figure 1. On balance, counties that experienced relatively large increases in house prices over the past year also experienced relatively large declines in inventories available for sale.

Conclusion

History shows a long-run relationship between house prices and the number of houses available for sale. Thus, current inventories of homes for sale are low given more than a year of house price appreciation. County-level data suggest that many homeowners are waiting for prices to rise further in their markets. Markets that have seen the strongest house price appreciation and job growth are the ones where for-sale inventories have declined the most.

More Than Meets the Eye

I endorse the Fed’s conclusion. However, the Fed’s research analysis does not go far enough.

Inventories in some areas are low because “investors” are snapping houses up expecting further appreciation. Some of this is large scale investment like Blackrock, but Flippers are in the game too, especially at the high end.

Momentum trading is back in vogue as noted in “Bubblicious” High End Flipping Up 350%, Overall Flipping Down 13%.

Flipping is up at the high end but renting is up overall. As long as home prices keep rising the renters and the flippers and those buying on spec will do well. But ….

What About Demographics?

Who are the flippers and investors going to sell to? Aging boomers? Their kids fresh out of college with no job?

I suggest we are in the midst of an echo bubble that can only last as long as QE lasts, as long as Boomers keep on living, as long as cities don’t collapse under pension obligations, and as long as taxes do not soar in an attempt to keep cities and pension plans alive.

How long is that? I really don’t know. But it is far, far shorter than the life of the average mortgage. And even for all cash buyers, demographics suggest that rising rents are hardly a given.

Mike “Mish” Shedlock

http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot.com