Germany is at the heart of Europe’s political predicament. Although the status quoa cannot and will not work, there is no incentive to change.

Germany’s Constitutional Court has strengthened the Eurosceptics and eliminates further moves by Germany towards debt mutualization.

Some think debt mutualization, eurobonds, and combined fiscal budgets are a good idea. Others, like myself, don’t. Regardless, and as noted in Rethinking “Paper Tiger”, those options remain off the table.

What remains on the table are policies that fuel high unemployment and undermine living standards says Brigitte Granville in Poking the Eurozone Bear.

Some take the sanguine view that the current “lie still” approach is adequate to ensure that the eurozone economy does more than avoid decline. From their perspective, Germany’s decision over the last three years to permit actual and prospective transfers just large enough to prevent financial meltdown will somehow be enough to enable the eurozone finally to begin to recover from a half-decade of recession and stagnation.

But the fact is that these transfers – that is, European Stability Mechanism-financed bailout programs and the European Central Bank’s prospective “outright monetary transactions” (OMT) bond-buying scheme – can do little more than fend off collapse. They cannot boost economic output, because they are conditional upon recipient countries’ continued pursuit of internal devaluation (lowering domestic wages and prices).

Reinvigorating the eurozone economy requires a more radical effort to resolve the interlinked sovereign-debt and banking crises. Specifically, it demands sovereign-debt mutualization through Eurobonds, and thus the elimination of eurozone countries’ fiscal sovereignty, and a full-fledged banking union with recapitalization authority and shared deposit insurance – a far cry from the arrangement that has been agreed.

If Europe’s leaders continue to choose mild palliatives over bold tactics, the best-case scenario is a lackluster recovery, with GDP growing at a 1-2% annual rate. Unfortunately, this best case probably is not enough to prevent future sovereign-debt defaults in countries like Italy, Spain, and eventually even France. In other words, at some point, lying still will no longer be an option.

As it stands, Europe’s political class is committed to internal devaluation in all of the troubled eurozone economies. The alternative approach – dismantling the eurozone to allow for external devaluations – has thus become the playground of hitherto marginal political parties, which are now surging ahead in opinion polls.

In France, the groups concerned – the National Front and the Union of the Left – represent political extremes. In Italy, a more ideologically neutral anti-establishment force may arise, with a much sharper anti-euro focus than Beppe Grillo’s populist Five Star Movement, which emerged last year to become the country’s third-largest political force. As these parties gain traction, the euro’s chances of survival diminish.

In 2011, Edmond Alphandéry, a former economy minister, declared that a eurozone exit by a member country was as likely as a dollar exit by Texas or California. Here, on full display, was the wishful thinking that brought the euro into existence in the first place: its French architects dreamed of a Europe that could equal the US. That was always an illusory ambition, but it continues to cloud European leaders’ judgment.

The single currency’s advocates are right about one thing: political motives have always underpinned the establishment of monetary unions, from Latin America’s in the period from 1865 to 1927 to that between Ireland and Britain from 1922 to 1979. But they are missing a crucial point: politics is also the reason for these unions’ dissolution. When the economic costs and divergences become too much of a threat, the political will to do what it takes to ensure the common currency’s survival collapses.

Voter reaction against the euro may well force the eurozone to stop lying still and take real action. The question is whether that would mean that some or all eurozone countries must go their separate ways.

Germany’s Pyrrhic Victory

Also on Project Syndicate, please consider Germany’s Pyrrhic Victory by Marcel Fratzscher.

The German Constitutional Court has ruled against the European Central Bank’s pledge to buy potentially unlimited quantities of distressed eurozone countries’ government bonds, and has called on the European Court of Justice (ECJ) to confirm its decision. Until that happens, the “outright monetary transactions” (OMT) scheme is effectively dead, weakening the ECB’s ability to act as an effective and credible financial-market backstop at a time when European governments remain unwilling to fill the void.

How financial markets will digest the German court’s ruling remains uncertain. There may be little initial reaction to the news, as there is no immediate threat to financial stability in the eurozone. But the big question is how markets will react in the future to bad news, whether about sovereigns or banks.

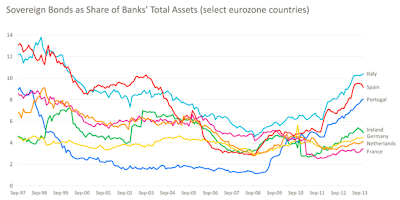

The tight feedback loop between sovereigns and banks in eurozone countries has become even more salient in recent years, as banks are holding an ever-larger share of their home countries’ government bonds. The ECB’s impaired ability to address sovereign and currency risks means that it will have to break the feedback loop via the banks – a more difficult and less effective approach that increases the likelihood of a market panic and a deeper crisis.

The German court’s ruling jeopardizes the ECB’s ability to act as an effective lender of last resort, thereby reducing its independence and ultimately undermining its ability to deal with market panics and crises – and thus to fulfil its primary mandate of price stability. The ruling makes it more urgent than ever that European governments establish a viable and effective banking union and strengthen the ESM as a backstop for countries in crisis.

When is the Breaking Point?

Notice the silliness of Fratzscher’s last statement. He begs for a viable and effective banking union, when it should be perfectly clear the German constitution court won’t allow for one.

Eventually something is going to break, and most likely at the worst possible time. Yet no one can say when. Meanwhile the imbalances continue to grow as complacency rules.

Spain 10-Year Government Bond Yield

That decline in yield looks like a good thing. But it comes with a huge risk. Spain’s banks have plowed more and more into its own bonds. When yields rise, those banks are going to be in a huge amount of pain.

Here are some charts from Squaring the Circle.

Sovereign Bonds Held by Domestic Banks

Sovereign Bonds Held by Domestic Banks as Percentage of Assets

As long as yields decline, there are no problems. The crisis will be even bigger than before if and when yields rise. When that happens is anyone’s guess. That it will happen is a near certainty.

One way or another Germany is going to pay a huge price. Theoretically, there are two solutions.

- Germany can pay the price by debt forgiveness and mutualization of debt

- Germany can pay the price via default when the eurozone breaks apart

If Germany will not allow option number one, the only viable choice is option number two. It would behoove Germany and the eurozone to have this discussion. Instead, Merkel has her head in the sand.

Mike “Mish” Shedlock

http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot.com