People have made all sorts of arguments against “monetary offset,” but there’s only one that actually makes much sense. The argument is that the Fed does not like doing “unconventional policies” like QE, because they feel “uncomfortable” with a large balance sheet. (Put aside the fact that QE is perfectly conventional monetary policy–open market operations—and that there is no reason at all to feel uncomfortable with a large balance sheet. The Fed is effectively part of the Federal government.)

Nonetheless, there is a sort of plausibility to the theory; Fed officials will occasionally say they would cut interest rates further if they could. But what is the implication of this theory? It seems to me that this theory implies that Fed policy should become much more aggressive when the Fed is no longer hamstrung by the zero bound. When they can stimulate without adding to the balance sheet. But this raises an interesting paradox—the Fed is conventionally viewed as being “stimulative” when they cut rates. Thus the Fed should want to cut rates as soon as they can do so, which means right after they raise them!

Of course I’m half-kidding. More realistically the implication is that once the Fed stops doing the “uncomfortable” QE, there will be a long period of zero rates before they raise them. And perhaps there will be, but right now the Fed suggests it will be raising interest rates in less than a year.

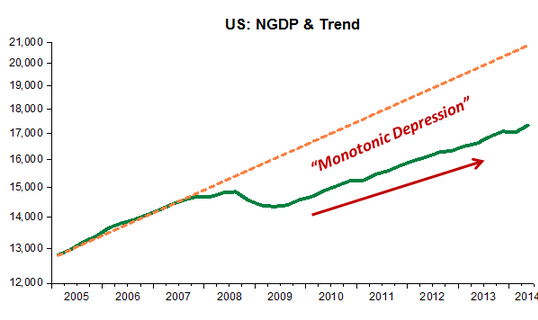

Here’s a graph from a Marcus Nunes post:

NGDP had been rising at about 5% per year in the 17 years before the recession, and it’s been rising about 4% per year in the “recovery.” Because wages and prices are flexible in the long run, the real economy has been recovering despite the lack of any demand stimulus. We have fallen from 10% to 5.9% unemployment. But most people think the economy is still in the doldrums, and needs more stimulus. President Obama just instructed the Department of Labor to increase unemployment compensation benefits (without any authorization from Congress of course–why do you think would Congress be involved in spending decisions?) This was done because unemployment is at emergency levels, requiring extra-legal remedies.

NGDP had been rising at about 5% per year in the 17 years before the recession, and it’s been rising about 4% per year in the “recovery.” Because wages and prices are flexible in the long run, the real economy has been recovering despite the lack of any demand stimulus. We have fallen from 10% to 5.9% unemployment. But most people think the economy is still in the doldrums, and needs more stimulus. President Obama just instructed the Department of Labor to increase unemployment compensation benefits (without any authorization from Congress of course–why do you think would Congress be involved in spending decisions?) This was done because unemployment is at emergency levels, requiring extra-legal remedies.

Fortunately the Fed is no longer doing the “uncomfortable” QE policy, which adds to the balance sheet. So if you believe the fiscal policy advocates, the Fed should be raring to go with stimulus. How do they do that? By promising to hold rates near zero for a really long time, or until the labor market is really strong. But instead, they are suggesting that they will probably raise interest rates soon. There will be no attempt to get back to the old trend line; the new one seems just fine.

Let’s consider an analogy. A bicycle rider has a “policy” of maintaining a steady speed of 15 miles per hour. Then he hits a long patch of ice, and slows to 10 miles per hour, perhaps due to a lack of traction, perhaps because he decided to go slower. How can we tell the reason? How about this, let’s put a strong headwind in his face, and see if the speed slows even more. But now he petals harder and keeps maintaining the 10 miles per hour speed. That suggests it’s not a lack of traction. But the pessimists insist it must be a lack of traction, why else would he have slowed right when he hit the ice? Then the bicycle final comes to the end of the ice. The lack of traction proponents expect him to suddenly speed up, exhilarated by the sudden traction of rubber on asphalt. Oddly, however, the bike keeps plodding along at 10 miles an hour. Nothing seems to have changed even though the ice patch is long past.

[In case it’s not clear, the headwinds were the 2013 austerity, and the end of the asphalt was the end of the liquidity trap.]

Here’s my claim. The Fed promise to raise rates soon is not the sort of statement you’d expect from a central bank that for the past 5 years had been frustrated by an inability to cut rates. (Nor is their other behavior consistent—such as the on and off QE.) Rather it’s the behavior of a central bank that has resigned itself to pedaling along at a slower speed. Ten miles per hour is the new normal.

I don’t want to sound dogmatic here. Obviously monetary offset is not “true” in the sense that Newton’s laws of mechanics are true; the concept only applies in certain times and places. Oh wait, that’s true of Newton’s laws too . . .

Opponents of monetary offset face two big problems. In theory, the central bank should target some sort of nominal aggregate, and offset changes in demand shocks caused by fiscal stimulus. And in practice it seems like they do, as we saw in 2013, even at the zero bound. So if monetary offset is not precisely true, surely it should be the default baseline assumption. Instead, as far as I can tell 90% of economists have never even considered the idea.

PS. Totally off topic, I love this sentence from an article on why a million dollars no longer makes you rich:

Although it sounds like a lot of cash, $1 million of today’s money is only worth $42,011.33 of 1914 dollars, which is less than today’s median household income.

Someone should collect all these amusing claims in the media. They could have added that today’s median income of $42,011 is only equal to $1764 in 1914 dollars, roughly equal to the per capita GDP (PPP) of Haiti. I guess I was wrong, the American middle class really is struggling.